|

||||||||||||||

| submissions | Tumblr | |||||||||||||

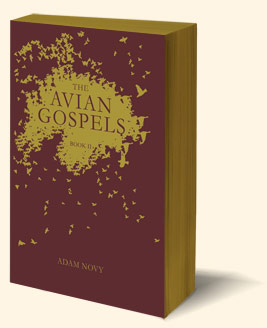

The Avian Gospels

Adam Novy

A city without a name is cursed by a plague of birds they probably deserve. But when an angry beggar child and his father learn they have the power to lift the curse—they “control” birds—they cannot agree on how to use their gift, and end up using it on each other, taking out everyone around them, especially those they love. Adam Novy lives in southern California. This is his first novel. |

|

|

Book I: |

Book II: |

|||

|

||||

|

Order through the Hobart website and receive a code for free e-book download. |

||||

reviews

“Imagine an alternate world in which Hungary borders on Oklahoma, where Norwegians and gypsies are secretly linked, where the cultural codes we think we know are reconfigured to become defamiliarized, and where characters slowly morph into their opposites. The Avian Gospels is about the birth and death of a religion, the birth and death of a city and the people in it. Novy's novel explores the way that myth is made and unmade, and is an impressive debut.”

– Brian Evenson, author of Last Days, Fugue State, and The Open Curtain

“Wildly imaginative, emotionally complex, gorgeously captured and crafted, Adam Novy’s two-volume literary aviary — so stuffed with birds you’ll want to keep your handsome copies nailed to the table lest they fly off or at you — is one of the most original novels I’ve read in months, maybe years.”

– Laird Hunt, author of Ray of the Star and The Exquisite

“I write from the aftermath of The Avian Gospels’ last sentence. There are feathers and blood on the floor, my location: a jackknifed timeline on shaken tectonic tiles. I have seen the horrors of broken fidelities to kin and creed, brutal sights of carnage and betrayal. But I have also seen soaring, beautiful, sculptures—sights never before imagined or dreamt. I blame Adam Novy for all of this.”

– Salvador Plascencia, author of The People of Paper

“You could call what Adam Novy's doing magical realism, but he writes as though the Latin American Boom never happened. In the world of the Avian Gospels, fire drools, houses wander like a mind, and the map has been rearranged so that China, Oklahoma, and of course, the dreaded Hungary butt up against each other in constant war. Even more striking, the novel contains all the pleasures or more conventional stories -- suspense, romance, violence, and slapstick. While the news he proclaims is not exactly good, Novy has written an authentic gospel for our time.”

– Christian Tebordo, author of The Awful Possibilities and We Go Liquid

"This debut has the potential to become a cult classic... a fascinating examination of what makes a martyr, a myth, or a legend."

– Publishers Weekly

"...like a cross between The Birds, The Road, and The Stand, except way more out there."

– Jason Diamond, Vol. 1 Brooklyn

"If providing readers with hope for the world is one of the great dishonesties of contemporary fiction, then Adam Novy is as honest as they come."

– The Rumpus (read full review)

"...like a cross between The Birds, The Road, and The Stand, except way more out there."

– The Nervous Breakdown (read full review)

"... a dark dystopian novel with birds. It has raw language and violence that's not for the squeamish."

– Birdbooker Report, The Guardian (read full review)

"... like a cross between The Birds, The Road, and The Stand, except way more out there."

– The Nervous Breakdown (read full review)

articles and interviews

"Adam Novy's The Avian Gospels, published in two pocket-sized volumes made to look like the Bibles you find in hotel drawers (faux-leather covers, gilt page edges, etc.), is no evangelical manual-for-living, but a "gospel" of a distinctly literary sort: a work of imagination and allegory, transforming contemporary America into a fantastical world."

read full article at TimeOut Chicago

“I've always wanted to write a sequel to the Bible. There's a poppy, grindhouse aspect to it, crazy things are always happening — Lot's daughters, Job, the Tower of Babel, the death of Moses, Christ, etc. — it's terse and violent and engrossing in the same way as, like, zombie movies or Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”

read full interview at Vol. 1 Brooklyn

“A narrative masterpiece with a healthy dose of social commentary on politics, class systems and war, the visual imagery in The Avian Gospels is filled with elaborate death scenes, horrific violence, scores of attacking birds, underground tunnels and well, some sex.”

read full interview at Dossier

excerpt

(originally published in American Letters & Commentary)

Our God surpasses the Gypsy god; He is more avuncular and noble, though some of us begrudgingly admit their god is more assertive than our God, whom we haven’t seen or heard from since He rose from His own corpse and promised to rescue us from peril, and He has, though in secret, and if you could witness His wondrous methods you surely would fizzle in awe, so decent and grand is He, our Savior, who speaks in a voice that is no voice, not the song of any bird, not the snap of burning logs or crunch of shoes on sand. God’s voice is silence, the silence beyond silence, the noise beyond noise, the darkest of the darkness, the inner soul of light. Yet, we have come to see their god as a local force to reckon with, and so we have arrived at a practical détente. We do not pay homage to this junior divinity, this petty and vindictive astral despot, this bureaucrat, slumlord and smiter of hope, we simply acknowledge he is there, though the mere fact of his thereness confirms the scandal of being there, and vindicates our God, who, instructively, is not there, is not only not there, but is nowhere near there, is anywhere but this tainted, soiled and sold-out world of matter. We assay their demiurge with irony and ardor; his powers are apparent, we are desperate for life.

And so, the endless war finally ended. Hungary tired of slaughtering us, and we them, though, in truth, slaughter came more naturally to them, which unpleasantly surprised us, we thought we were great at slaughtering. When the good news arrived, we poured into the streets, dancing and singing and carrying flags. Few of our streets could be marched on, though, for most had been destroyed, and lay beneath rubble. All of us, it seemed, had seen buildings come down, cobblestones flying, livestock hurled into the sky by explosions, soaring pigs, fragments of neighbors’ homes blown through our walls; most of us had seen our possessions turn to ash, had stood atop the heaps of shattered heirlooms. We tried to salvage books and maybe chairs, but as for pianos, grandfather clocks, tables, beds and mirrors, few of these objects survived. We soon forgot the details of these blasted belongings, the blemishes, inscriptions, and little private histories, we even forgot the scent of rubble, though, most nights, we stand beside these ruins in our dreams, the music of forgetting in our ears.

It’s true that we had suffered, yet there were days when pain seemed distant as we waited in bread lines or for updates from the front, our children playing at our feet as we observed with that mix of pride and dread that parents have. Some of us even held cookouts or parties, while others formed teams or wrote poems beneath oaks, though this we discouraged, or tried to discourage, though the more we discouraged it, the more people did it, so then we ignored it. That worked better. There was always music playing, always a band of trumpets, trombones, tubas and drums, saxophones and fiddles, and, for the men, a belly dancer; the instruments manned by Gypsies, and how we hated Gypsies, and suspected them of things, and wished they would bathe, though few had running water, they all lived in ghettos. We so needed music in those days, and still do; the Gypsies play better than us, but that only demonstrates the emptiness of experts. Fluency in the songs of God does not bring you close to God, only in the poverty of meekness before Him can you feel His awesome force, which can’t be captured in song. We are not a musical people; music is their god, their temptation, their blasphemy; music is frivolous, fatuous, sacrilegious, though if you are standing in a goulash line, or working, relaxing after work, making love or praying; if you face hardships, music can soothe you, providing you know its low place in God’s scheme.

The parade at the end of the war was not grand, like those of the past, with ranks of cheering citizens and proud, resplendent soldiers. We scrambled from our lean-to’s and foxholes, waving flags and humming, the melody growing in volume with our numbers, a widow here, some children there; the civic leaders gathered in what remained of the government building, just the façade of that once-proud, two-block long, canary-colored edifice, a smoke-slaked wall alone among the wastes, the columnar porticos blown out like missing teeth. When our soldiers returned, we lined the few passable streets and stood atop the handful of buildings, rejoicing. Revelers hung from light-posts or scurried up drainpipes, all of us hoisted toasts to God and hurled confetti, even the Gypsies, whose numbers increased by the day.

There was one woman who resembled a Gypsy but swore she was a Swede; this maybe-Gypsy milled about the crowd with her husband, following the melodies of our songs, but not the words, for the Swedes had just arrived and, unsure of everything, affected to enjoy local customs, though they didn’t comprehend or even know them. We will assimilate, they’d said during their journey through the woods, across battlefields and mountains, prairies and rivers, stepping over bodies, the whole Earth a cemetery, all the aquifers clogged with bodies, and nearly every brook and stream and creek dammed with corpses, the stars their distant weak companions, their child so near to birth.

I think it’s time, she said on the day of the parade; she’d known for hours, and had tried to hide the pain from her husband, for what with the festivities, to make a scene would be dangerous. She couldn’t bear the throes of birth, and squeezed her husband’s wrist. Pain came in thrusts as they shoved through the crowd, it stomped the air from her lungs. Her husband was so fragile, he wept at any setback, a gentle man, The Gentle Birdkeeper; Hey gentle birdkeeper, she said, I’m about to have this baby. She leaned against him and he helped her through the crowd to the abandoned storefront café they had claimed as their home, where she lay on the table and bit her own hand to keep from screaming.

Her husband looked scared. What should I do, he asked. Tell me to push. Push! Push! She pushed. He rummaged behind the counter and found a pitcher of water, which he brought her, What am I supposed to do with this? I don’t know, it seemed like the right thing to do, bring you water. AAAAAHHHHHHH! she cried, Honey, tell me what are we to do, are you okay?

I’m fine, she said, between the blasts of pain, find a knife, you’ll need it to cut the lifeline. She could hardly get the words out, so great was the pain, which erupted in regular bursts. Together, they had endured storms, bandits, battlefields, interrogations, natural formations too strange to name, hidden jets of steam and boiling mud, only for her to lay on this table, a parade outside, her husband behind the counter, searching for a knife. They had been the objects of scrutiny since arriving. No one who traveled the wilderness was safe, anyone who survived it seemed in league with its dangers. Her husband returned with a knife. She squeezed his hand through the latest crescendo, the edges of her vision redly blurring. Perhaps you will blend in without me, she thought, but didn’t say it, he wouldn’t take it well, he didn’t take anything well, though he tried hard, his intentions were good, she did love him, he’d done everything he could for her, God knows it had not been much. The pain came again, she fought it by screaming and clutching her husband, trying to keep the darkness at bay for long enough to have the baby.

It won’t be long now, she thought. I’m scared, he thought.

What was he going to do without her, she wondered. The storefront café where they lived was no place for a baby. Where would her husband get food? The agony came again; the intervals were shrinking, too brief now to be intervals, or even pauses; moments, maybe. Breaths. She would’ve said she loved him if such words did not embarrass her, and what the hell did any of this matter now, she was shrieking, shrieking, sweating, thank God the noise of the parade drowned the sound, Get over there and be ready, she gasped, he left her side and bent before her womb, her throat felt shredded, she wouldn’t need it anymore, she pushed, she pushed, oh God, there it was, her husband had it, he lifted it, Slap it like I told you, he slapped it. Harder, she said, it has to cry. We only know it’s living if it cries. He slapped harder, on its hip; terrified, as ever, by the ruthlessness of life. The baby cried. It’s a boy, he said. She felt a smile bleed across her face, so odd a feeling. Already, color seeped from the flat plane of her vision as if sucked by a straw.

But we do not weep at your untimely death, Swede; you who were unchained from your body and freed, as from an Egypt everlasting. It is we who are doomed, and you who are released, we who,spirit-corpses, toil beneath the living, brandishing our phantom-knives at plethoras of nothing, and you who see the Earth from above, clenched and pulsing, like a sparrow’s heart.