|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | news | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Rhinoceros |

|||

|

Sweet Venus |

|||

|

Forever Girl |

|||

|

List of 50 (3 of 50): DEFECTIVE DATABASE PARTITION |

|||

|

Ray Vukcevich |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

Sometimes We All Go Kaboom

I used to have these inclinations. I would sit down to write a story, and something would occur to me as right and proper for that story. And I would think about writing that thing that seemed right and proper to the story. And I would think to myself: “Well, I can’t write that.”

For whatever reason, I shied away from offering to a reader what was right and proper for a story because I worried. I worried, maybe, that they wouldn’t take the story seriously. I worried, maybe, that I would lose them.

And then that story ended. I lost that story to my worry. It went into the filing cabinet, where I imagined it would stay forever.

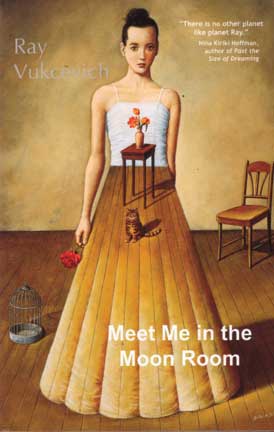

And then I read Meet Me In The Moon Room. The short stories of Ray Vukcevich are masterworks of surrealist art. They are written in an alphabet that after Z loops back on itself in a moebius strip, branches out in three dimensions, and includes those characters cartoons use when they swear.

And yet.

And yet they are so much more than exercises in imagination. Ray Vukcevich can also—with the sudden emotional revelation—break your fucking heart.

Over the last few months, I have been interviewing Ray about a very short, very good story called “Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Boy.”

Describe your work to me, if you think you can.

Well, here goes. Protect me from myself if this comes off stupid or pretentious. I spend almost no time writing about writing. In fact, on my business card (which people told me I should have, so I made one, but it wouldn't be hard to calculate the precise number of them that I've ever handed out) there is my name and contact info on the right and the word "fiction" on the left. So, who knows if my answers to your questions will make any sense at all?

Most simply, what I'm trying to do with my stories is give the reader something she or he has not seen before. I read for different reasons at different times. I can appreciate the perfectly executed example of a known form, and sometimes that's just what I want. Usually, though, I'm looking for a peek into a very different mind. I think there may be other readers out there looking for that, too, and those are the readers I'm usually writing for.

Have I noticed that since Rumsfeld seized power, people are all the time asking questions and then immediately answering the questions themselves? Yes, I have. Do I find myself doing that, too? Sadly, I do. How about you? So why do I think that I can offer anything a reader hasn't seen before? And why do I think this is a good thing? I answered those questions in a "pep talk" email to my workshop last year or maybe the year before.

I told them that it all starts with these facts.

No matter how smart you are, there is always someone smarter. No matter how good looking you are, there is someone who is better looking. No matter how nice you are, there are nicer people. Pick a field and realize someone is doing a better job than you in that field. There is always someone (but not always the same someone) who can say, "I can do anything better than you." And with one exception, they will be telling the truth. The one thing that no one can do better than you is be you.

All you've really got is a unique point of view.

But that's really quite a lot. It means you are an entire universe. It means you have all the time there is. It means you can say things no one (really, I mean no one) else can say. You are so amazingly valuable (I told my fellow workshoppers). I so much do want to hear about what it's like to be you. And this is the foundation, in my humble opinion, of innovation in art.

To paraphrase one of my favorite movies (Cronenberg's Naked Lunch), you go to the Zone, you take a look around, you figure out what it's like, and then you file a report. That's it. Sure, there are other things you can do like reading as much as you can. And, yes, since we're talking about fiction (which is all talk, after all) there are issues of language to think about all the time—we can drive ourselves crazy with them and we probably should. But it's really a matter of going into your own zone and filing reports back to the waking and waiting world. We should leave the boring parts out of our reports.

It wasn't long before a friend pointed out that Saul Bellow had said something very similar years earlier, but without the bit about the Zone and leaving out the boring parts. Oh, well.

I guess I shouldn't stop without giving a writing tip. I always let my computer read my stuff aloud as a late step in my process. Ah, ha! I knew it. People always give me that what-are-you-crazy look when I spill those beans.

Let's focus on one story: Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Boy. The story begins with a flood, a downpour of words from a single, manic narrator.

ICBM Boy has always reminded me of a band from Washington DC called The Nation of Ulysses, who were famous for their live shows. The live performances were much more than just high energy. They teetered on the edge of total collapse into riot. Mic stands were swung. People bounced off each other. They had a lyric: "I'm a bottle rocket, baby. Light my fuse." And that's what they were. Explosives waiting to leap into the air and go boom.

If you can recall, tell me a little about the genesis of this story. And then, I'd like you to say something about the dizzying quality of long, long sentences.

Me: I wrote " Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Boy" to be read aloud.

You: are you nuts?

Yes, you have to sneak in a lot of quick breaths to keep the flow going—little snorts of air, really—hey, I wonder if readers of such sentences could learn circular breathing like didgeridoo players? Reading ICMB Boy aloud reminds me of the way some baroque woodwind music is written like the flute players don't need to breathe. Just keep tooting, guys. When I wrote the story, it was all happening on the page and in my head, and then I got up and read it. My workshop has two or three readings a year where people bring short shorts and read them and then we eat cake or whatever. It's usually Halloween or the winter holidays. I've forgotten the occasion for ICMB Boy, but textual clues tell me it was probably Santa season. Maybe it was all the strange looks I got that made me think Strange Horizons might like it.

I think the "dizzying quality" of long sentences really is a matter of air. The long sentence in ICMB Boy is about breathlessness—a headlong rush, unbalanced, arms windmilling. It's not even, strictly speaking, grammatical. This is like the base case, the raw example, of how I work in general. I suspect it's very much like Tourette's syndrome, but until someone convinces me it's a problem, it's not a problem, it's a feature, a plus, I mean I usually meant to do that. I get the babble, gabble, rabble going (or more precisely, I just let myself notice it) and then I write down what I hear. No, that's not quite right. I write it down, and if I don't like it, I loop back to snatch up more from the same spot before we are all swept downstream where the talk is all about something totally different. All long sentences are probably not about breathlessness, but they may all be about breathing. Could we make a case for that? Maybe we should learn Spanish, or more Spanish, or polish up our Spanish, so we can test that hypothesis with The Autumn of the Patriarch because how do we know if breathing actually translates? So, there you have it. We should probably move on before I go kaboom.

Does this question make sense: with a story like "Intertcontinental Ballistic Missile Boy," does the character inform the structure, does the structure create the character, or is there a way in which they act as cooperative engines of creation?

The structure and character inform each other, I think, but how something turns out is not always how it was made. It's fairly common for me to start with words that just come to mind. "I hope it isn't raining. . ." followed by the realization that the hope is futile, and after that, the modification of the hope—if it is raining, something else might not happen, but, of course, it will. The story proceeds like that to the end. And if that was that, you might call it "automatic writing"—me typing whatever foolishness pops into my head—but ICBM Boy was not close to finished after that first rush of words. There are probably twice as many words scattered around the work area as there are in the finished story. I really do believe written fiction is all about language—in a way, it's all talk. I shoot for getting exactly the right words in exactly the right order. I also like to say I don't "rewrite."

So, isn't that a contradiction? Not really. I don't think of what I'm doing after the first rush as "rewriting". Instead, I think of it as "more writing." I keep writing until I'm finished. So what's the difference? The trouble with writing and then rewriting is that the first part is fun and the second part often isn't. Writers can set themselves up to suffer by breaking the process into two pieces. If it's all one thing, it's all fun. Or it's all not fun—life is sometimes hard.

I know people who take a very different view. For them revision is the truly creative part of the process. The joy is in the rewriting. I say, if that works for you, go for it, even if I do worry that if the fun part is the rewriting, the less fun part must be the writing. For me, it's all one thing that I keep doing until I'm done.

Here's the question of reliability. ICBM Boy is a strange little character. Should we trust him to accurately describe his world? Should we trust you? How much does that matter to you? How much do you want to give away, and how much do you want to keep buried beneath the surface of a story?

Okay, what I ideally want is for you to just accept the whole thing from word one. Yes, trust me. You can think of the character as an unreliable narrator, but he is not lying to you or to himself. You can also get a bigger picture by imagining yourself looking down on him from above. That kind of reading can be fun, too, and there is enough in the text to justify it. For me, a "reading" is between the text and the reader. I am sometimes surprised at what people come up with. I like writing that invites you to simply come to the world in question and be there now. I recently read Clifford Chase's Winkie, for example. Here you need to just accept the walking, talking, thinking teddy bear and go from there.

Can you think of other examples?

Three of my favorites are Emmanuel Carrère's The Mustache, Kazuo Ishiguro's The Unconsoled, and Damon Knight's Humpty Dumpty.