|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Are You Lonesome Tonight? |

|||

|

Space is Our Future |

|||

|

The Weirdest Thing |

|||

|

Sunsets Unlimited |

|||

|

489 Points |

|||

|

Rain Escape |

|||

|

They Shared an Egg |

|||

|

First Book Roundtable Discussion |

|||

|

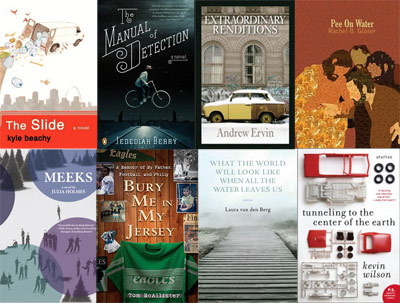

Kyle Beachy is the author of The Slide (The Dial Press, 2009). He lives in Chicago and teaches writing and literature at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Univeristy of Chicago's Graham School, and Roosevelt University. His short stories and essays have or will appear in St. Louis Magazine, Another Chicago Magazine, as a Featherproof Mini-Book, and elsewhere. |

|||

|

Jedediah Berry's novel The Manual of Detection (Penguin, 2009) won the William L. Crawford Award and the Dashiell Hammett Prize, and is a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Award. His short stories have appeared in journals and anthologies including Conjunctions, Chicago Review, Best New American Voices, and Best American Fantasy. He is an editor at Small Beer Press. |

|||

|

Andrew Ervin's first book, a collection of novellas titled Extraordinary Renditions, will be published by Coffee House Press in September. His fiction has appeared in Conjunctions, Fiction International, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Louisiana, but that is about to change. |

|||

|

Roxane Gay's first collection, Ayiti, will be released in the Fall of 2010 (Artistically Declined Press). Other work appears or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, DIAGRAM, McSweeney's (online), Gargoyle, Annalemma and others. She is an assistant professor of English at Eastern Illinois University and co-editor of PANK. Find her online at www.roxanegay.com. |

|||

|

Rachel B. Glaser is the author of Pee On Water (Publishing Genius Press 2010). Her stories have appeared in 3rd Bed, New York Tyrant, Unsaid and others. She currently lives in Easthampton, MA with the author John Maradik. |

|||

|

Julia Holmes was born in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and grew up in the Middle East, Texas, and New York. She is a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA program in fiction, and lives in Brooklyn. Her first novel, Meeks, will be published by Small Beer Press in July. |

|||

|

Caitlin Horrocks is author of the story collection This Is Not Your City (Sarabande 2011). Her stories appear in The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories 2009, The Pushcart Prize XXXV, The Paris Review and elsewhere, and have won awards including the Plimpton Prize. She lives in Grand Rapids MI, where she is an assistant professor at Grand Valley State University. |

|||

|

Holly Goddard Jones is the author of Girl Trouble, a collection of short stories. She teaches at UNC-Greensboro. |

|||

|

Tom McAllister's first book Bury Me in My Jersey: A Memoir of My Father, Football, And Philly (Villard/Random House) was released in May 2010. His shorter work has appeared in several publications, including Black Warrior Review, Barrelhouse, and Storyglossia. A 2006 graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he is currently a Lecturer in the English Department at Temple University in Philadelphia. |

|||

|

Laura van den Berg was raised in Florida and earned her MFA at Emerson College. Her fiction has appeared in One Story, American Short Fiction, Conjunctions, Best American Nonrequired Reading 2008, Best New American Voices 2010, and The Pushcart Prize XXIV, among others. Laura’s first collection of stories, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us (Dzanc Books, October 2009), was selected for the Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Program and long-listed for both The Story Prize and the Frank O’Connor Award. She was the 2009-2010 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College and is the recipient of the 2010-2011 Tickner Fellowship at the Gilman School. |

|||

|

Kevin Wilson is the author of the story collection Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (Ecco/Harper Perennial, 2009). His fiction has appeared in Tin House, One Story, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. He lives in Sewanee, TN. |

|||

|

Mike Young is the author of We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough (Publishing Genius Press 2010), a book of poems, and Look! Look! Feathers (Word Riot Press 2010), a book of stories. Recent work appears in American Short Fiction, LIT, and Washington Square. He co-edits NOÖ Journal and Magic Helicopter Press. He lives in Northampton, MA. |

|||

"BEGINNINGS"

|

|

Thanks for agreeing to have this conversation. The topic of first books is one I thought a lot about as were planning this issue of Hobart. It's been a lot of fun, as a reader and as an editor, to see you guys get books out into the world. As I was thinking of the list of writers to ask to participate in this conversation, I was struck by how different each of your books was from the others. Some of them are more traditional story collections, some are novels, or hybrids forms, or novellas; they range in genre and style, some of you have books with big New York publishing houses and some of you are with small or indie presses. You're quite a group. So, just to situate us a little, would you mind talking a little about your books? What it is, who put it out, etc.

Kevin Wilson: I have a collection of what I would call traditional short stories (Tunneling to the Center of the Earth), which was published as a paperback original by Ecco/Harper Perennial (Ecco bought and edited it and Harper Perennial put it out).

Laura van den Berg: I'm also the author of a story collection, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, published as a paperback original by Dzanc Books in October.

Holly Goddard Jones: And me. My story collection, Girl Trouble, was published by Harper Perennial in September, also as a paperback original.

Kyle Beachy: Sounds like paperbacks for days. Mine is a midwestern novel called The Slide, published by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, in February of 2009.

Julia Holmes: Hi, everyone. My first book's a novel called Meeks (to be published by Small Beer Press in July), which takes place in an ultratraditional society that requires bachelors to marry by a certain age, or else become civil servants and work under the thumb of the Brothers of Mercy — a kind of nefarious, fanatically chaste Salvation Army.

Roxane Gay: My first book is a collection of short stories and a little poetry and a couple pieces that are neither fish nor fowl, called Ayiti all about Haiti and/or the Haitian diaspora experience. It will be released this fall by Artistically Declined Press.

Mike Young: I've got two books coming out, both with small publishers. We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough (Laura, we need to talk about the trials of having way too long titles!) from Publishing Genius Press in Summer and Look! Look! Feathers from Word Riot Press this Winter.

Tom McAllister: My first book is a memoir titled Bury Me in My Jersey: A Memoir of My Father, Football, and Philly, the subtitle of which pretty well sums up what the book is about: the life of an obsessed Philadelphia Eagles fan. It's being released by Villard on May 18, so I'm right in the thick of all the exciting build-up — doing PR stuff, getting my hopes up way too high, etc.

Caitlin Horrocks: My first book is a collection of short stories, This Is Not Your City, that was at one point going to be out in Fall '09 with a university press. When the press got its funding axed, the book needed a new home, and happily found one with Sarabande Books. The new release date: an agonizingly long wait until spring/summer 2011.

Jedediah Berry: My novel The Manual of Detection was published by Penguin Press in 2009, and came out in paperback this year. It's a surreal mystery story involving dream detectives, file clerks, an evil carnival magician, and an alarm clock heist.

Andrew Ervin: Sorry to join the party late. These projects sound amazing. I've had the pleasure of reading Tom's memoir in galleys and recommend it highly. My book is a collection of three novellas, Extraordinary Renditions, which Coffee House will publish in Sept.

Rachel B. Glaser: Don't worry Andrew, I am even later! I'm excited for MEEKS, I've heard great things about it. My book is a collection of non-traditional short stories called Pee On Water, coming out this June/Sept from Publishing Genius Press.

Thanks, guys! These all sound so good. Some of these I've read and the others all sound fantastic. Roxane, I'm really interested in this idea of a book that is stories, poetry, a little bit of this and that, all tied together maybe less by form or plot than, say, theme or obsession. At what point in the writing of the pieces in Ayiti did you think you had a book on your hands? Also, what does Ayiti mean?

Roxane Gay: Ayiti is Creole for Haiti. It is pronounced EYE E T, sort of. I mention that because I've heard some interesting pronunciations. I felt like I had a book on my hands when I realized I had written a strange little set of pieces on Haiti and they were all vaguely depressing which is my general obsession as I try to make sense of the Haitian struggle both in the US and in Haiti and my place in all that. The number of pieces I had written about Haiti surprised me because relative to my overall output I don't write about Haiti very much. I'm almost hesitant to because my experience is as a Haitian American and I'm always negotiating an understanding of my country from a position of real privilege; I'm learning from my parents (who still live there part time) but what do I really know? Anyway, the more I looked at this body of work on Haiti, the more I thought, this is something and the only thing I could ever call it was Ayiti. I sent the manuscript to a couple publishers who gave me great feedback but declined the manuscript, then I mentioned it on my blog about rejection at which time, Artistically Declined asked to see the manuscript and a few hours later, snapped it up. It's a Cinderella story in all the best ways and that's how I knew it was really, truly a book. It was a matter of finding the right fit.

For those of you with story collections, did you find much resistance from the publishing world? Is what they say true? Are story collections difficult to sell? Actually, let's open that up to the whole group. Julia, you're with Small Beer, which has a pretty distinct aesthetic, it feels like (feel free to correct me). Did you find any resistance to Meeks as you were sending it out? Kyle, your novel The Slide, which I loved a lot, does not feature the Brothers of Mercy, but does none the less reach a pretty great level of strangeness at times. Did you have any resistance to the book as you were sending it around for these reasons? What about the rest of you? Any war stories from the front lines of first book publishing?

Roxane Gay: I can't say I've encountered much resistance because I haven't submitted my manuscripts very much this year on account of trying to finish my dissertation. Of all the manuscripts I have lying in wait, this is the last one I expected to be picked up so quickly and I'm still not entirely convinced a book is going to happen because it feels so surreal. I did send it to a few places and there was some resistance — too ethnic, too grounded in realism, too this, too that, we no longer publish fiction, etc., but I didn't feel any specific resistance to the idea of a short story collection or I tuned that resistance out because I love short story collections and I'm stubborn. That said, my full length short story collection which I am "shopping" around is certainly meeting with resistance if by resistance you mean constant, soul destroying rejection. I call it resistance training. It builds muscle.

Mike Young: I sent a manuscript to Jackie Corley at Word Riot Press in September 2008. In December 2009, she sent me an email back saying she wanted to publish it, which was terrific. The manuscript had changed considerably since then. In fact, there was a new manuscript, with only a couple stories from the original. To make things even more exciting, my new manuscript wasn't exactly "done." So I asked Jackie if I could send her the new manuscript to look over (I should've asked this paragraph if it was okay to use the word manuscript so many times) when I finished it. She said sure, then she contacted me via Gmail Chat the next day or something and said "hey mike, i'm confident in your writing style so let's just say that we're officially pubbing your book and you're just delivering the revised final manuscript to me in jan." Of course, I didn't end up delivering her a final until April.

Holly Goddard Jones: Selling my book took about two years. I got an agent right out of graduate school, before I was really ready for one, and that was part of the problem. And this agent, who was older and very established, just wasn’t the right fit for me. I don’t think that she was used to hand-holding a young, insecure writer, and I wasn’t mature enough to be my own cheerleader. I also tried in those two years to write a novel, and I got about 100 terrible pages in before I realized that I was going to have to toss it. That, I think, is the biggest pressure on the writer with a book of short stories: to produce a novel, or an idea for a novel that’s so great that a publisher will take your stories on the promise of that other project. Anyway, it’s a long story, but now I’m with a different agent, and—for good or ill—my editor bought just the stories, not the stories as part of a two-book deal. Of course it would be nice to have the security of a contract for the novel, but the good thing, I guess, is that I didn’t have to force a second project that I didn’t believe in to sell the first project that I did believe in.

Laura van den Berg: I had a pretty lucky, low-resistance experience with my collection. In 2007, after winning the Dzanc Prize for a work-in-progress, they asked to see the rest of my collection and made an offer shortly thereafter. In the meantime, I had been taken on by a great agent, who has been an invaluable part of the process. Like Holly, I sold just the stories, for better or worse, even though I had, at the time, started the novel I’m now revising; the 2-book system seems to work beautifully for a lot of people, but I was a little freaked out by the notion of committing contractually to write a novel when the project was still in its early stages, and fortunately Dzanc was wonderful about doing the stories alone.

Kyle Beachy: There were certainly times during my stretch of rejections that I found comfort in some analogue of that notion, strangeness. Mostly I tried to drop my head and reduce the process to a numbers game: there are this many agents and I can send out this many query emails and all of this rejection is technically part of what it means to publish, and so on. But I was never immune to the soulcrush, nor rationalizing my way out of it. It's extremely easy to bemoan the tastes of others. Circumstances, too – I remember a few particularly sad moments when I frankly and truly blamed Zach Braff. But of course there are a thousand reasons a publisher or agent won't stand behind a manuscript, and rarely does strangeness cover them. The truer issue was that my book still needed a lot, lot of work, and I had to find both an agent and editor who were up for it. And I think that even at my darkest moments I recognized how strange was too easy an explanation. It's the same self-service we get from experimental, sometimes, or avant-garde, these kind of therapeutic jumpsuits we zip ourselves safely inside then refuse to take off and launder, even after we've sweated through and the stench has turned rank.

Tom McAllister: I don't have a story collection, or enough good stories to comprise a readable collection, but I'll chime in here re: war stories, I've been fortunate not to have much difficulty on that front. The greatest frustration was waiting about 21 months for the book to finally come out — about 2 months longer than it took me to actually write the thing. They wanted to market it as a Father's Day gift, and when I signed the deal in mid-September of '08, they said we didn't have quite enough time to release it by '09... although one could argue that if 9 months is enough time to conceive and gestate a human child, then maybe it ought to be enough time to put a cover on a book and print it, but I know I'm oversimplifying things. But definitely for me the most frustrating thing about this whole business is the glacial pace at which it moves. I'm an impatient guy — the primary reason I queried my eventual agent is because no one else had responded after several months and I read somewhere that she gives quick rejections via email. I just wanted someone to acknowledge that my query existed, I guess.

Caitlin Horrocks: When I finished the first version of my collection I'd absorbed the conventional wisdom that story collections on their own (no novel) were an impossible sell, and that my best and only chance at publication was to enter the manuscript in contests. So I did, and won one, and then seven or eight months later things went south. By that time I had an agent, and she sent the collection around to some places. I was expecting 'no's, and got them, but what made the process difficult was that most of the rejections weren't "not right for me" or "not my thing." Editors liked the stories, sometimes really, really liked them, but we always circled back to the problem that my story collection was a story collection. I had a synopsis for a novel that my agent sent with the stories, and everybody agreed that that book sounded pretty great. Unfortunately, I hadn't written it yet. Happily, Sarabande embraced the collection with open arms. Overall, I ended up feeling that the resistance to short story collections was both very real and overstated. It was a problem, to have a book of unlinked stories with no novel waiting in the wings, but I got fair reads and more encouragement than I'd expected. I wasn't laughed out of town, which is somehow what I'd thought happened to short story writers.

Laura van den Berg: Not to stray too far from the question at hand, but Caitlin I totally agree with your feeling that the resistance to collections is both "very real and overstated." The resistance is a real thing to be sure, but there's also support for the story out there. After all, each year collections get published by houses big and small, win awards, get reviewed, etc. I'm not totally convinced that story writers have it that much harder than everyone else.

Caitlin: Laura, totally agreed. And it seems like one thing guaranteed not to help short story collections is for all the people who write and read and like and buy them to talk constantly about how no one else reads or likes or buys them.

Kevin Wilson: The collection wasn't difficult to sell, as long as I also had the promise of a novel. Ecco, I don't think, would have taken the collection if I didn't have 100 pages of a novel to attach to the deal. It was like this for most of the other publishers. They liked the stories, but wanted a novel to go with it.

Andrew Ervin: The idea of how to label a book is a tricky one. And by "tricky" I mean "market-driven." It wasn't Moby-Dick: A Novel or Leaves of Grass: Poems, right? My three novellas sold because combined they sort of resemble a novel. The publisher refuses to put "three novellas" on the cover; that's a bit of a disappointment, but I also completely trust my editor and now that he's doing what he thinks is best to get the book in most peoples' hands.

Rachel B. Glaser: I was blindly, amateurly, boldly sending my collection around. It was exciting anytime I could send it to a familiar name and say something that pretended that I was connected to the editor in some way. Then, brilliant Mike Young suggested I send it off to Adam Robinson (of Publishing Genius) who had written online that he had enjoyed some of my poems. So, in that way I luckily avoided the prejudice against stories collections, that I've heard so much about.

Julia Holmes: Meeks went out to 25 or 30 publishers over a two-year period — some of the rejections were thoughtful, even helpful, but a lot of them cited the "problem of strangeness" in one way or another. I'd sort of expected that, and I started to notice that, from opposite sides of some writer/publisher divide, we were all treating "strangeness" as a self-evident problem. That seems like a bad habit, and I agree that it's an easy expectation to get caught up in — and, of course, it's true that strangeness can be shorthand for all kinds of things. But I feel like whatever resistance existed closed certain doors and ultimately pushed the book in the right direction, and it ended up with exactly the right publisher and editor. I don't have the benefit of a big-house experience (for comparison), but in the case of Meeks, I think having the chance to work with a smaller press was a huge advantage.

Tom (welcome, by the way!), this brings up a really interesting aspect to the process, I think. Have you others experienced a similar pace from sale to publication? My guess is there's no across the board answer, but I'm curious about how many of you found things to be like Tom did.

Holly Goddard Jones: It took about a year from contract to release for me, which seemed like a good amount of time. I wouldn't have wanted it to be faster. In fact, now that the book is out, I have to say — sorry, Tom! — that I enjoyed anticipating the book's release more than I've enjoyed having it out in the world.

Jedediah Berry: I spoke with several agents about my novel before signing with one of them. It was a process I took a good deal of care with, because the manuscript wasn't finished (this was during my last year of grad school), and I knew my agent would be among the few people who were reading and providing feedback on the novel as I completed it. I feel I lucked out here, because the agent I went with understood what I was up to, and he's a great editor. Then he found an excellent editor for the book. So, no real battle scars to show off. Writing, and rewriting, and rewriting: that was the hard part.

Kyle Beachy: I'm with Jed (may I?) here — though I'm curious how your interactions with your editor played out. Was there a good deal of back and forth once he / she bought it? I know the first thing my (young and very smart) editor sent me was a ten-page, single-spaced memo about the book, which made clear both how well he understood what I was trying to do and how much he believed remained to get done. I recall my stomach plummeting. Of course now I'm grateful he put so much time into my revisions... the book needed them.

Jedediah Berry: You may, Kyle, and yes, that sounds familiar. I think we did four rounds of edits on the book, and much of it was substantial: there are three completely different versions of the penultimate chapter now moldering on the trash heap. But the most important thing my editor did was to point out when something didn't make sense to him: when he lost sight of a character's motivation, or when some aspect of the story didn't add up. He asked important questions, and they were questions the book needed to have answers for.

Kyle, you and Jed seem to have had similar experiences as far as feedback from agents and editors throughout the editing and revisions process (others, please join in here too). I'm curious about how it works. Notes from editors and rewrites, rewrites, more rewrites. We've talked a little already about the time between sale and publication. So, what happens, exactly, during that time? Frantic re-writes and much nail-biting or are we talking martinis by the pool and regular ego stroking calls from an editor?

Tom McAllister: For me, there wasn't much re-writing. My agent had me work up one chapter she didn't think was so great, but that was it. My editor had some suggestions, most of which were quite helpful, and some of which were terrifying (i.e. "I think you should maybe cut all of the Iowa stuff," which, at that time, was 25% of the book, and which ultimately I didn't do), but he only had me do two re-writes, neither too drastic. One benefit of the very long waiting period was that I had generous deadlines on the re-writes, which was nice. Anyway, outside of the editing, I'd say I spent maybe 13 of the 21 months doing nothing related to the book; I just started working on the next book. I heard from the editor maybe every 6 weeks, usually just him checking in to reassure me that my book still existed; I think he could sense my impatience, so he tried to placate me now and then.

Tom McAllister: Oh, forgot to add (sorry, I know my answers are getting long), in the remaining 8 months, I found myself doing a lot of semi-tedious stuff. Reading the galleys enough times that I don't think I'll ever want to read this book again, begging people for blurbs, getting permissions to quote and use names, talking to the legal dept. (favorite question: "In chapter 4, you say your Uncle Mike is a loser. Can we find some way to prove that?"). The most fun part for me was having some input on the cover and seeing it come to fruition — giving the book a cover seemed to legitimize it.

Laura van den Berg: Well, there were martinis, but they weren’t served poolside. Rather it was my own recipe, severed in giant water glasses. But back to writing! I worked on the stories with my agent and then my publisher had some light notes. I also had a good amount of time between the acceptance of the collection and having to turn in the final manuscript, so I read and re-read the stories and then revised and revised. For some of the stories, I completely re-wrote them and there was one in particular that I just couldn’t get to work and was certain I'd have to drop from the book. But I re-wrote and re-wrote and then, at the final hour, something finally clicked. Once the manuscript was turned in and we’d gone through the production process (helping with the cover was super fun!), the promotion process began, which is an adventure unto itself.

Kyle Beachy: I realize this exchange isn't geared toward a focus on this distinction, but I wonder if people agree that one key difference between the major and the independent publishers is the fact of having a dedicated editor? Do people agree that smaller presses are less likely to nudge a manuscript one way or another? I'm wondering if the sense I'm getting here is generally true...Laura, your phrase "light notes" strikes me as particularly hands offish.

Holly Goddard Jones: Working with my editor at Harper, Sally, was absolutely the best part of the experience. I thought that she was a perfect reader, one of the best I've ever had — thoughtful, wise — and she asked all of the right questions, so that I could revise in a way that still felt very personal. I never felt steered into a vision that wasn't mine, but I felt at every turn that I'd put the book into the hands of a person who really loved it and wanted it to be the best version of what I could produce. I know that I was very, very lucky to have her, and I say all of that because I think the belief about small presses versus New York presses (one I harbored) is that a NYC press will never provide that level of care, especially to a no-name writer of short stories. Perhaps my situation was anomalous, but that aspect of getting a book into the world was just about ideal.

Kevin Wilson: I'd gone through a lot of edits with the editors who published the stories in journals. Then I had a long back and forth with my agent (who I think is an incredible editor and we work really well together). Once it got to the publisher, there weren't many changes made. On one story, we changed the gender of the narrator. That was it. I felt the editor was reading it very closely, and we had many discussions about it, but I also felt like I had spent so much time with the stories, that it was hopefully already in a good place.

Laura van den Berg: I had a similar experience as Kevin, in that I had done lots of edits on the stories with magazine editors (after the title story was accepted, for example, I probably did 6 or 7 drafts with that editor) and then edits on the entire manuscript with my agent (a great reader and editor), looking at everything from revising individual stories to what to drop/add to the way the stories should be ordered. By the time the manuscript reached Dzanc, they felt it was in pretty good shape, so the lack of an intensive editing process didn’t feel so much “hands off” as an expression of that sentiment. However, I, nervous wreck that I was, kept editing until the final hour.

Kyle, to go back to your question, I do think it’s true that at indie presses, the staff are usually wearing multiple hats, so you might be less likely to find someone whose job is exclusively editing. On the other hand, I have talked to friends who published with indies—Graywolf, Coffee House, Sarabande—that had intensive editing processes, so I would imagine it’s a case-by-case thing with both the author and the publisher more than anything else.

Jedediah Berry: By day I'm an editor with Small Beer Press, and I can say that I work closely with my authors on the editing of their manuscripts. It's true that I also act as publicist and events coordinator, and I do layout and design, but then everyone at the press does some of all those things, so the ideas are always circulating and being built upon. If anything, I was worried that I wouldn't receive that same kind of attention when I went with a big press for my own novel. As it turns out, I learned a lot about editing from my editor at Penguin, and have been able to put some of those lessons into practice at Small Beer.

Tom McAllister: Kevin (and others, of course), I'm curious to hear more about the "many discussions" you had with your editor. You didn't make too many changes, but apparently spent some time negotiating over the lack of changes; was any of that contentious? How did you go about vetoing suggested changes? Was your editor receptive to your ideas, or did you really have to fight for your work?

Kevin Wilson: Hey, Tom, the discussions were mostly about making sure that I was happy with the final product, since it was my last chance to make any changes to the text. We also talked a lot about the collection as a whole, where to put stories, how one might rub up against another in a more pleasing way than a different story. So, I think our discussions were more about the larger identity of the collection and not on specific stories. It was not a contentious process at all. Part of that was because, in the beginning of the process, I was so happy to be published, that I would have accepted just about any changes as long as I got my picture on the back of the book, but I got over that quick. Mostly the process was easy because I got along with my editor and neither one of us is a person to dig in our heels on a specific issue and we were working hard to understand our sometimes opposing positions on certain stories. We just talked about what I wanted to do with the stories, what she then thought they were actually doing, and how to make everything line up. I think I'm not answering this well because we also spent a lot of time talking about babies, because we were both close to having a first child. We also talked about hamburgers and which ones we wanted to eat and which ones we did not when I eventually came to visit her in New York.

Andrew Ervin: It's fascinating to hear how other editors work, thank you all. (Almost two years in Louisiana and I still find the word "y'all" repulsive, yet am perfectly content with my native-Philadelphian "youse." But nevermind.) My agent made some amazing suggestions and then I asked my editor to get angry with my ms. and edit the bejesus out of it. He went easy on it, though, and I learned a great deal from his insights and those of the proofreader. At a certain point, like Tom, I was unable to read it anymore with any clarity. I'm hoping for a second wind before I have to go out and do readings and try to make people excited about spending their sixteen bucks.

Roxane Gay: My editor has given me some great suggestions on my manuscript but I think I'm more brutal with the editorial suggestions than he is because I am so nervous about putting this book into the world.

We can actually get some feedback from both editor and author. Jed, you and Julia have been working together on Meeks, right? What's the editorial process been like from the other side of the table, so to speak? And, Julia, have you found that your experiences so far have matched up with what's been said?

Julia Holmes: I think they do match up for the most part — it's been a great experience (with lots of rewriting). I have to say, working with Jed has been fantastic. It's hard not to go into an editorial relationship with a certain amount of anxiety — who is the person, how does s/he think about things? Early on, we talked sort of broadly about the structure of the book, how to handle the transitions between narrative voices (there are a few in the book), and that conversation put me entirely at ease. After that, it seems to me that we went through three or four rounds of revisions (over 9 or 10 months, maybe), all pretty major, in the sense that the structure of the book changed each time, whole narratives came and went. But the questions Jed asked really transformed the book — seemingly innocent (or maybe I mean lucid/ straightforward) questions about how the book, or the world of the book worked. And then I'd go off to start rewriting, and I'd realize they were incredibly complicated questions. They went to the heart of the matter, and they were hard to answer, but restructuring the book around them made all the difference — and they also showed how deeply he was thinking about the book on its own terms, which meant a great deal. And because I trusted his judgment, I was comfortable going in and yanking out parts of the book that had been there so long I'd started mistaking them for vital organs. But maybe the aspect of the process that surprised me most was the encouragement to experiment more (not less) as the process went on, and it was liberating to take chances, try things out, even close to the deadline. I think you have to have an abiding faith in someone's judgment to do that. I always felt like we were both thinking about the book in similar ways, generally interested in the same kinds of problems — though maybe a great editor makes the process feel collaborative in that way. Sometimes I felt like we were fellow engineers on a weird malfunctioning rig in the North Sea — but in the most pleasant sense. Anyway, for my part, I feel incredibly lucky things worked out as they did — it's been a pretty ideal first-book experience in that regard.

Jedediah Berry: To stick with that image of a pair of engineers, which I love: I tried to be the fellow crouched over the tool bag, handing up wrenches and hammers as needed, and maybe at most saying things like, "What you need now is one of these right here" or "Just a little further to the left." In other words, I wanted to make use of my experiences while keeping my particular writerly inclinations out of the equation as much as possible. I fell in love with Julia's book because I was completely convinced of her vision. I felt it was my job to help her achieve that vision as fully as possible—to get things moving, and then to get out of the way. It was an exciting process, and I'm very proud of the results.

Really helpful answers here, all (or youse or y'all, depending). Interesting discussion about edits and revisions, and where they came in the process. Kevin, I think your mention of the collection's identity (and TttCotE really came together well for me in this regard — the stories in this book build on one another in great ways, they feel like they fit together just right, hitting similar notes, but never the same one, if that makes sense) is really interesting. I wonder how true this for others, too. How much editorial energy was put into the identity of a collection as opposed to individual stories? Much of this, I would guess, also depends on the book itself, as well as the particular writer. I don't know. Thoughts? And to jump from there to another question: Laura and Tom, you both mentioned getting to work pretty closely with your publishers on the cover design. Has this been (or is it currently) true for the rest of you? How closely to you get to work on the physical book itself?

Kevin Wilson: Thanks, Jensen for the kind words. To answer the cover question, the cover design process, for me, was a little embarrassing. Ecco sent me an email and asked if I had any suggestions. Boy, did I. I said I hoped it might look like an old pulp novel or a comic book from the 50's. The title seemed to have that kind of ridiculous promise of an adventure tale, and I wanted to do something weird with that. I suggested about fifteen comic book artists and then mentioned some cover artists for pulp novels that might still be alive. I must have said the words "comic book" about a hundred times. I sent this email, like a ten page email, and then a week passed, and then they sent me an email that said they had some other ideas and they would figure something out. And then they showed me the cover and I realized how dumb I had been, and how beautiful their cover design was. Working on the physical book, I didn't do much. I didn't have much of an opinion. I remember my agent really pushed for french flaps (this may not be the correct term) and fancy paper and I remember not knowing what she was talking about. Of course, I wanted the book to look nice, but I didn't really know how to make that happen. So I relied on the book design people and I'm glad I did.

Roxane Gay: In my case, the collection always had a strong identity because all the pieces are, in some form or fashion, about Haiti. In that, my editor has, I think, put more energy into the individual stories, helping me tighten them and make sure they work together as well as they can. My editor has also been great in letting me be involved in the cover design. My mom took the picture that will be used as the cover image so that's a really nice thing for me because the book is dedicated to her and it thrills me that she can be involved in this way.

Laura van den Berg: With my collection, a good amount of time was spent shaping the book as a whole. I definitely wanted the stories to have a kind of interconnectedness, to be in conversation with each other, but also hoped to avoid too much same-ness. We tried to craft the book in a way that seemed cohesive but not redundant, which informed the order of the stories and also cutting a story that my agent and I agreed was more repetitive than helpful to the larger enterprise early on. In my case, the stories are all working with recurring thematic elements, so I would imagine the prospect of repetitiveness might not be as much of a concern in a more varied book.

Kyle Beachy: I pushed for a skateboarding buddy of mine, the cartoonist Anders Nilsen, to get a shot at the cover. So he did and my editor was into it, everyone was into it, and then the oddest thing happened: one of the country's larger book retail outlets said they didn't like the cover, enough that they'd reduce their order unless we changed it. Which is odd, I think, perhaps a bit backward w/r/t my naive understanding of capitalism, when one retailer's share of the market is dominant enough to dictate the nature of the good itself. But then 2008's financial crisis cut into the retailer's book orders across the board, and suddenly we weren't so beholden to their tastes, and we could return to Anders' cover once again.

Tom McAllister: Sounds like my experience was similar to Kevin's, in that I offered some ideas, but mostly they did all the work. Mainly, my ideas focused on what I didn't want on the cover. From the start, I've been very concerned about it being pigeonholed as "just a sports book," which carries a certain stigma for a lot of readers, and so I stressed that I didn't want some generic sporty design (and no author photos in my Eagles jersey!). But mainly, they just did what they thought would look good, then came back to me for feedback. They did the same with the interior layout, fonts, etc. I trusted them (far more than I trust myself) when it came to graphic design, but it was very gratifying to be consulted about it and to feel like part of the process.

Holly Goddard Jones: I had a pretty set vision of the book by the time it got to my editor — I think that's how a collection of stories ends up getting representation, actually. It has to feel like a book, a cohesive whole, and not some decent stories that have been stitched together. Sally and I went back and forth a bit about the ordering of some of the middle stories, but most of that was initiated on my end, and it stemmed from a discussion that we were having about the title of the book. Harper's marketing people didn't like the title. Sally did like it, and of course I liked it — I wouldn't have called it Girl Trouble if I hadn't liked it — and that was the most distressing issue for several weeks. They wanted me to give the book a title that was longer and more lyrical, like another book that was coming out around the same time as mine, and I like those titles, but I'm not that good at coming up with them. And rethinking the title was making me rethink the central themes of the book. If the book had been called Life Expectancy or something, which was a title I considered, would the unifying themes of masculinity and womanhood and kinds of victimhood be as apparent? It wasn't that I loved Girl Trouble so much that I was resistant to considering another title; I just didn't know how to find a title that would unify the books' themes the way that one, for me, did.

This is actually a good segue to the cover business. After weeks of hearing that the title had to go, I suddenly heard that there was a cover design, and the marketing people thought that the cover made the title seem suitably weighty. So, out of nowhere, the title wasn't an issue anymore. They presented me then with what is more or less the cover as it is now, minus the Claire Messud blurb. I liked it well enough. I wasn't sure about the yellow, but it seemed fine to me. But the cover/title combo has been a major pain since the book's release. If I have to explain to another 60-year-old man at a book fair that it's not a children's book or a romance novel, I'm going to shoot myself. And so many of the reviews and articles have begun with a statement like, "Don't let the title fool you." I feel stupid for not anticipating this response, but it honestly never occurred to me that so many people wouldn't grasp the irony of the phrase, "girl trouble."

Jedediah Berry: In a strange way, I influenced the design of The Manual of Detection because there's a guidebook called The Manual of Detection within the novel, and my publisher printed the novel so that it resembles the guidebook as I described it. The power of metafiction, I guess.

Mike Young: Adam Robinson of PGP and Jackie Corley of Word Riot Press have both been suave and helpful in their understanding and editing of the individual pieces and their conception of the books as wholes. Adam in particular has been very good at pointing out where poems line up with other poems and how to emphasize or stray from such relationships. Just like a real relationship counselor. Mostly I've been given gracious carte blanche regarding cover design, though Adam and Jackie both have firm and welcome ideas of how they think things should look. Adam wanted me to change the title font from something more distressed to something more firm and confident. Again, all are welcome to think of that in personal advice terms. For the stories, my friend Bryan Coffelt is helping with the cover design, and as of right now I am actually not sure what he's going to do, but I am excited, because he grew up where I grew up in Northern California, and the stories take place around there, so I'm hoping he'll grok onto Nor Cal's particular strangeness and whip up something suitable. Plus Bryan's studying book design right now, and he's already designed awesome covers for Evelyn Hampton's We Were Eternal and Gigantic and the Schomburg/Frey co-chapbook Ok, Goodnight, so there we go.

Julia Holmes: I've been a fan of Robyn O'Neil's work for a long time — she has an amazing series of graphite drawings, all populated by these doomed-seeming men in black suits roving a hopeless, post-apocalyptic landscape (that always felt evocative of the world of Meeks, its doomed bachelors in matching suits). I'd always loved the idea of using her work on the cover. Small Beer and Jed were open to the idea and designed a beautiful cover around a detail from one of Robyn's drawings.

Rachel B. Glaser: Adam Robinson of Publishing Genius has been very amazing about the whole decision-making process, allowing it to turn into an ongoing dialogue. He has given me a generous amount of say, and I really appreciate him including me in the process because I have learned so much about publishing. Holly, I can understand your feelings about your title. My title "Pee On Water" got very extreme mixed reactions from people. A room of my most admired writing teachers would insist on me changing it, but then a "Pee On Water" supporter would speak up to me, passionately, and I would have to agree. It's difficult to change titles after you've had yours for a while, in my case, years. I seriously considered changing it, coming up with dozens of replacements, but none seemed so epic or particular as "Pee On Water," which is the title of a story in my book, which in terms of scope, is bigger than all the others. In the end, Adam allowed me to design my own cover [Editor's note: you can see that cover right here and also pre-order Rachel's book, which I highly recommend), and I am proud and embarrassed to say that I worked on it for over 200 hours, updating to constant new versions.

Caitlin Horrocks: The earliest version of my collection was essentially my MFA thesis, which was “here are the twelve best stories I’ve written in random order.” At the time, I hadn’t written all that many more than twelve stories. The book has evolved since then to the point that, as my editor and I shuffle the line-up, I can look at some of my newer stories and feel like I have a grip at least on what won’t fit. But much of that awareness of the-book-as-a-book has come through other readers; the stories are all so individual for me I still sometimes have trouble seeing the connective tissue. One of the reasons I love short stories is that I can take on different challenges or voices or structures in each one, and I worried that would result in an unwieldy book. It’s been a great but eerie experience to have other readers point out that the stories share certain themes, or that multiple characters face similar challenges. Readers have seen more cohesiveness than I did, and helped me see it, too.

Probably because the book is still a pretty diverse collection in my own head, I sent a ridiculously long email to Sarabande with about twenty different cover ideas in five different categories. Miraculously, they seemed to take them all seriously, and the current cover design is based around one of them.

Dan Wickett has a post over at the Emerging Writers Network about Southern Methodist University Press. What's happening at SMU is obviously a potentially really sad (and all too common) development in the publishing world. Caitlin, your collection This Is Not Your City was going to be published by a university press before the press lost its funding. Luckily, Sarabande picked it up. Unluckily, we all now have to wait a longer to read the book. Would you mind talking a little about the process? I don't know how much detail you want to go into, but the story sounds interesting. How did Sarabande end up with the book? Did you have to start the process over again?

Caitlin Horrocks: Beware!: Super long answer. It was a long story. I’ve been especially sad to see the news about SMU Press—they’re a great press, I had an essay in an anthology they did, and I’m obviously really feeling for the authors involved. SMU was also one of the presses that friends and colleagues suggested I might want to try with my collection when EWU-P was folding. No one there ever saw it (Sarabande ended up with it first), but I’ve been imagining this bleakly funny parallel universe where someone there liked the manuscript and my book died twice. I’m glad I’m not the Harbinger of University Press Death.

The first big sign of trouble with EWU-P came last spring, when my agent learned that my contract still hadn’t been countersigned after a long delay; when she tried to get in touch with her contact person, she was told that the press had been “downsized.” I then called the managing editor, who told me that the press was going to be shut down after a year-long grace period in which two staff people would keep their jobs long enough to wind down the operation. There never seemed to be any formal announcement or official communication to the authors involved.

Over the next couple of months there was a lot of uncertainty about whether the press would receive a reprieve, or what would happen to the lists when/if it closed. The managing editor was unfailingly kind and competent and helpful in a situation that was bad for me, but obviously much worse for her. EWU-P was still planning on publishing my book, but it was going to be the last volume out the door before the lights were off and door was locked.

My agent started to send the book to other publishers, but in the end I had to make a decision about whether to pull the book from EWU-P without another press lined up. That was a scary decision, and people gave me a very different advice. Because I have a university teaching job, some thought I should go ahead and do the book through EWU-P, even if the book went instantly out of print, for job security. At the opposite end of the spectrum, some thought my writing career was best served by just sitting on the story manuscript until my novel was done. I hoped for a middle route: I loved and believed in the stories, and didn’t want to let the book die, but to go ahead with publication through EWU-P was in many ways letting the book die in a different way.

I pulled the manuscript in late July, and then had a couple of humbling months to mentally readjust to not having a book anywhere on the horizon. I realized how much self-assurance and writerly comfort that little word “forthcoming” had provided me. This past September, a friend with a connection to Sarabande Books offered to contact the editors to see if they wouldn’t mind taking a look at the manuscript. Sarah Gorham said yes, and then yes again to the stories, and I’ve been incredibly lucky and grateful to end up with such a happy ending.

This whole process explains my answer to your previous question about editing: by the time the book was with Sarabande, every story in it had been published and edited by journal editors, and arranged and rearranged. I’ve got my fingers crossed for light editorial suggestions at this stage—I’m not sure how much additional work I’ve got left in me on this set of stories.

I think I speak for many when I say that I'm happy that This Is Not Your City is on its way out soon! Speaking of having work left in you on a book: What's the touring/reading/promotion been like. Mike and Rachel, you guys are going to tour together this summer, right? Where are you guys going? What do you have planned? What about the rest of you? How was (or what do you plan to do) the promotional side of the experience?

Andrew Ervin: I'm grateful for this question, Jensen, because I'm really at a loss here. I'll get a little bit of money from my publisher if I want to do a couple readings in other cities and would be grateful for some advice from the people here about how to spend it wisely. Thanks!

Tom McAllister: Sorry, Andrew — I don't have any useful advice for you. I'm just jealous that you can get money to read in other cities. I've got some readings set up in the Philly area, but have found a lot of this promotional stuff to be DIY. I don't mean to imply that the PR people aren't working hard, but we've all read the many stories about not enough publicists, too many books, etc. Plus, the same office that's promoting my book is on the verge of launching a multimillion dollar vampire trilogy about two weeks after my memoir comes out, so I know I'm not top priority. That said, they have managed to get me well-publicized events at a couple of the big book stores: Borders in center city Philly, a big Barnes and Noble in South Jersey, etc.

As for the rest of the promotional stuff: I'm currently one week from book release, which means I'm just beginning everything. Mostly, this has involved me reaching out to every blogger and friend I know, having my editor and/or publicist sending copies to about 90% of the local media with fingers crossed, and checking my phone every 5 minutes just to make sure I didn't miss a monumental phone call about some PR breakthrough. Also, I did an interview on sports talk radio at 11:45 PM on a weekday, which wasn't nearly as bad as it may sound. This is a terribly disorganized answer, I think, which is maybe a pretty accurate reflection of my state of mind during this promotional process.

Laura van den Berg: The promotion was definitely a group effort. My publisher, agent, and I worked on a PR list for galleys and final copies and in addition to those mailing, Dzanc was great about advocating for the book and getting it into the hands of people who might be interested. They provided tour support, but there was a lot of DIY involved too. I did a fairly substantial tour, which was fun but involved a lot of planning. I also did things like contact media in the places I was visiting, e-mail bloggers with the offer to have a galley sent if they’d be interested, etc. The whole process can be a little consuming, in that there’s always something more that could theoretically be done, so I had to figure out how much I could do happily and then not worry about getting to the rest. Andrew, re your question, I think it makes sense to cluster events by area as much as you can, so if you’re doing a reading in Boston, maybe try to hit some places in the same region, as opposed to going to Boston one week and then going back the next week for a reading in New Hampshire or NYC. Also, for what it’s worth, I had really good experiences with reading series in respect to both turnout, since a good one comes with a built-in audience, and book sales, so I think they’re definitely a venue worth pursuing.

Holly Goddard Jones: I was pretty happy with HP's efforts to promote the book. In addition to the regular galley and review copy mailings, there were two direct mailings, one to southern writers and one to independent booksellers in the southeast, and a giveaway at AWP. The book was featured in some group advertising that appeared in venues such as Tin House, AWP Chronicle, and The Believer — I think that advertising of any kind is rare these days — and I was asked to do some guest blogging at Huffington Post, Book Club Girl, Book Reporter, etc. I also went on a regional book tour, with hit-or-miss results. My readings in Kentucky, Columbus, Ohio (where I went to grad school), and Tennessee all went well. My readings in North Carolina, where I moved in the summer of last year, were not so good. Kevin, I seem to remember you blogging about this subject, so maybe you can chime in on this, but bookstore readings can be the pits. People will tell you that the real value is in having your book on display in the weeks preceding the reading, and you also get the opportunity to meet book sellers who can be an advocate for you, but that's hard to remember when you're reading to two or three people. I've also done some book fairs and festivals, which can be awkward, but there's a benefit. At the Kentucky Book Fair, for instance, I met a person who ended up adopting Girl Trouble for his book club. Another arranged for me to do a reading at his city's public library. I think that the book business these days, especially when you have a collection of short stories, operates very much at the level of the hand sell, even if your press is commercial.

Laura van den Berg: Holly! I had the exact same experience re bookstores, save for the bookstore reading I did in Boston, which almost doesn't count since I used to live in Boston. For the most part, these were really wonderful bookstores that host readings frequently and I was usually reading with another author, but still they were by far the most challenging venue I encountered on tour. Sometimes there was an element of bad luck involved (i.e. torrential rain), but I have since wondered if other authors encountered similar issues, or if I had just made some sort of strategic error. There are for sure other benefits to bookstore readings, but I agree that it can be hard to keep that perspective when you have a super small turnout.

Kevin Wilson: The book tour, though I was excited to do it (my dad drove with me so we could spend some time together), was kind of soul-crushing in many ways. It had nothing to do with the publicity people at Harper Perennial (who were awesome and worked hard to get any notice they could for a book of stories by a first-time author) and it had nothing to do with the independent bookstores (the owners were always really cool and said they were pushing the book), but it was the sheer fact that most of the time almost nobody came to the reading. I don't blame anyone. I was a first-time author with a book of short stories. I was reading in places where I knew no one. But it was still weird. I have now learned what is worse, having no one come to a reading, or having one person. The answer is: one person. With no people, you can run back to the hotel and eat a pizza and watch tv in your pj's. With one person, you have to determine if they want you to read to them ("No, that's okay") and you have put a huge burden on that person to buy a book so you don't feel even worse. Over a hundred people came to a reading in Oxford, MS (where I read with another writer and there was music), and I felt like the greatest writer of all time. And then one person showed up the very next night in Blytheville, AR. I do think the tour helped in getting my name out to places that might not have otherwise considered pushing the book, and I hope I made an impression on the people who came to the reading, and I did sell some books, but it was a tough way to do it. My publisher helped me set up a few non-fiction things, and I had a piece in the New York Times Sunday Magazine and I think that was really helpful in getting notice for the book. And my hometown newspaper wrote a nice article for the front page and I probably sold as many books that way than I would have doing a bookstore reading.

Holly Goddard Jones: I kept feeling, as I did my mini-tour, that the bookstore thing was this holdover from another time — a ritual we all keep persisting with because everyone assumes that everyone else wants to do it. As a first-time author, of course I wanted to do it, at first, though I'll be more hesitant if I'm lucky enough to get a second book out. I don't think that the bookstore events were a priority for the publisher, and the bookstores, though (as Kevin said) always friendly and supportive, seem sometimes to do more of these gigs in a week than they can adequately publicize. It's hard to get review or feature coverage as a first-time author if you're one of five events that a store is hosting in a week.

Tom McAllister: Did you all read Stephen Elliot's piece in the NY Times (back in January) about what he called his DIY book tour? Brief summary for those who missed it: essentially, he made personal appearances at book groups and in people's homes, very much in the vein of a Tupperware party (or any variation thereof), and found it to be fairly successful, especially in comparison to the traditional tour. I thought it was a pretty interesting alternative to the heartbreaking ordeal of doing bookstore readings for one person in a strange town, but I wonder how viable an option it is for first timers and relatively unknown writers.

Laura van den Berg: That was a really interesting article, and it's interesting to me the various ways in which book promotion, touring, etc, are being re-invented right now. I actually feel like it's a pretty accessible model for the debut author, although it certainly helps to have cultivated an audience of some kind beforehand. Kathleen Rooney and my Dzanc label-mate Kyle Minor did a joint book tour that took them all over the country for their books Live Nude Girl and In the Devil's Territory, which was Kyle's first book; their thing was to have a local author read with them at each tour stop. It seems like it's more of a question of how much time/energy you are able/willing to devote to organizing a book tour. For example, I think Kathleen look a leave from her job to do the tour with Kyle. To organize something so extensive seems like you'd have to be willing to give your life over to the thing for a few months.

These are really great stories from touring/reading! Laura, I think you bring up a good example with Kyle and Kathleen, and Stephen's article speaks to this too; I wonder about this idea of re-invention/re-thinking of the book tour. This idea of reading (tour) as spectacle or event. Or maybe what I mean is making a lot of effort in unusual or creative ways. Everything from tweeting, facebooking, articles in newspapers up to big event-type readings like the Dollar Store Tour from last summer that Featherproof did, or Stephen's tour, or the way that Kathleen and Kyle did things. Anyway, I guess there wasn't so much a question in there as an observation.

Andrew Ervin: Is it just me, or does all this self promotion — "tweeting, facebooking, articles in newspapers up to big event-type readings" — feel kind, I don't know, dirty? I have the Facebook page and Twitter feed and I'm hoping that some cool magazines and blogs will interview me, &c. I want people to read the book, I guess, and so it's up to me to get the word out about it, and I'm totally doing that, yet it feels like self-promotion isn't what I signed up for when I started writing this thing. Are these qualms normal?

Kyle Beachy: There's definitely an egotism to the promotional process that has made me uncomfortable at times. I suppose it's not really all that different from the whatever's required to believe, hey these words I've written are worth your time — so sit down with my book and give me your undivided attention. But the avenues of promotion today are so wide and varied, with blogs and tweetfests and the universe of Facebook, that the task of self-promotion has achieved a new dimension, and it's constant. I admire the way that Stephen Elliot handled his tour, and I enjoyed his reading here in Chicago, but I frankly can't imagine the project of travelling the country and looking into all of these people's eyes and basically asking them to buy my book. Standing in living rooms and kitchens... I'd begin to feel like a vacuum man. There's a certain taint to activities that are based on commerce, and having a book out forces you to confront the fact of being a salesman. I wasn't ready for it. And this isn't to say Stephen wasn't making personal connections and reaching out to readers — which I bet most of us would agree is the whole point — but just that I worry how I'd handle such a sustained promotional tour. I'd get that tummy feeling. My favorite Faulkner bit starts with, "Read if you like or don't read if you like."

Mike Young: Wow, I have a totally different perspective on touring/readings than most people here, I guess. I've done plenty of shows—including lots of house shows—as a musician and a writer, and it's probably my favorite part of the so-called "creative process." Performance has always felt like a natural outgrowth of writing to me. If my work is talking at imaginary faces, then real faces are the mystical bonus round. Granted, I don't like hustling people to buy my shit, but I do like entertaining them. Entertainment comes from roots that mean "to hold among," to draw people in, to intertwine with somebody. That's why one of the nicest things a stranger can do is entertain us, because that means they're becoming less strange. Think of how you don't have to say anything when you and somebody else are both laughing, but how much you know about that somebody else that you didn't know before you laughed together.

I mean, maybe this is all just my weird taste. I'd love for The National to play in my livingroom, and I'd buy their CD if they did a good job. And, okay, I actually enjoy sleeping in kitchens and eating 7-11 jerky. I'd rather live in a snow globe than an apartment, etc. Which is ridiculous, sure. But I do agree with Kyle above that publication is, fundamentally, a very egotistical gesture. For me, readings—and other forms of direct contact with readers, but most especially readings—actually feel like (potentially) graceful manifestations of that gesture: here I am with this language I made. And I'll go ahead and make it again for you with my breath. That's always felt actually kind of amazing. Which is to say I try my hardest to be half as good as some of the really terrific readers I've seen. Plus, if the book sucks, I (the author) can be off on an island riding walruses while you (the reader) suffer with my sucky book. If my reading sucks, at least you have this warm human to hate, which is always more satisfying than hating a book.

Philosophy aside, the tour Rachel and I are doing with Natalie Lyalin is something we planned entirely ourselves, since all our books are out from small presses without PR people. I'm stoked for it. We're going to Philadelphia, Baltimore, DC, Richmond, Durham/Raleigh, and Atlanta. One reading will happen in a warehouse, another in a church, a few in houses. Rachel and I both live in Northampton, Massachusetts, so we decided to plan a tour that didn't include stops too close to home—New York, Boston, local, and so on—since we could read in those places whenever we wanted. We do have a Boston reading planned for August, and we'll be in Ann Arbor in September. Honestly, for me, this shit is maybe the most comfortable part of "having a book," the same way that singing songs to people is the most comfortable part of having songs stuck in my head.

One more thing: Stephen Elliot's tour struck me as beautiful in its simplicity and gusto. He took an indie music convention—the house tour—and made it work for literature. His particulars fit, obviously: he was touring a memoir that people could relate to, telling stories from his life that made people want to share stories from their life. But I think the model could work for fiction and poetry as well. I guess maybe it does require that you somehow have at least one friend or friend-of-a-friend in a lot of different cities. And it also helps, of course, if you're not boring. But like Elliot said in the piece, people love parties. I've seen and helped to make happen plenty of musicians touring by Greyhound, hopping from house party to house party, etc, and I don't see why that couldn't work with authors too. Actually, there are communities of authors who already do this: slam poets, chiefly. And I'm sure people have opinions about slam poets. So there are larger conversations to be had, I bet, about performance and community, being an open node and practicing enunciation, but those are big conversations and probably too annoying to address in the scope of this interview.

Kevin Wilson: Mike, it's not that I don't enjoy reading to people; I like reading out loud and seeing how the work seems to change as you read it to people. What sucks is reading to no one. My official book tour, which was very small because I couldn't get much time off from my job and I didn't want to leave my wife with the kid for too long, was a series of readings at independent bookstores. And so, yes, it was nice to read to people, but when people didn't come, I was standing there in front of twenty copies of my books while the staff drank beer and wondered when I was going to leave. I think, as Laura mentioned, the traditional book tour probably isn't the best way to do things for first time authors. Since the official tour ended, and I'm setting up my own stuff, when I've read with other people, read at places where music was featured, or read at schools where the kids were fun to be around, it was awesome. And I sold a lot more books in these ways than I did on the traditional tour. I think the tour you've set up sounds wonderful, especially the variation of setting. But, at the bookstores, which were, again, run by really cool people, there was still this idea that I was coming in order to help both of us sell books. And so, when that didn't happen, it was awkward.

Mike Young: Totally agreed, Kevin. I've also done things where no one shows up, and it sucks. And I think the point you mention at the end about an event that's thrown under purely commercial auspices versus an event that has other things going for it—all of the alternatives you mention revolve around notions of community—is a really apt insight. This reminds me of an essay A.D. Jameson recently posted on the litblog Big Other: "Alternative Values in Small Press Culture," which is a terrific cheat sheet of how to pursue other ways of doing this stuff, especially the stuff that we've been talking about as making us feel uncomfortable. Okay, the part about how we should do more yoga is a little weird, but the post is otherwise quite practical and lucid and exciting.

Rachel B. Glaser: I have never done a reading tour before, so it's helpful to read everyone's accounts. It seems sort of crazy to do so many readings in a row, and I wonder if I'll get sick and doubtful of my work. But then again, maybe you reach a different plane after many readings. Maybe you gain a new confidence and control that allows you to really throw yourself into your story's dialogue without getting self-conscious. Like male-voice, female-voice!

Laura van den Berg: I enjoyed the public process as well. I liked traveling about and seeing new towns and cities and meeting new people, both in the real world and via web stuff. The whole thing was a big adventure, and I’m always up for adventuring.

That said, when it comes to the web—e-mail lists, Facebook, etc—I do think there’s kind of an art to striking the right note. I have wound up on author mailing lists and feeling spam-ed in a sort of relentless and impersonal way. On the other hand, I get semi-regular communications from other authors and I’m totally happy to receive them; they feel more like friendly updates somehow. So at times I worried over reaching out in a way that felt natural, about bothering people too much, etc, but I didn’t really have qualms about diving in

On the other end of the spectrum, my partner is a fiction writer and published his first book—Once the Shore—last year. He and his publisher did work together on building the review copy list, etc, and he was very involved in the behind-the-scenes goings on, but he completely opted out of the public promotion stuff. He didn’t build a website or a Facebook page, didn’t tweet or do events. He’s not into that aspect of the process and whenever people would push him to do these things, he would say, “That’s just not me.” And his book didn’t suffer from that approach at all. Not one bit. So, at the risk of sounding naïve, I think it’s really important to be yourself and to do what you think you will enjoy, or at least not actively dislike, and what you think will be most effective for your book. One thing that’s emerged from the current publishing landscape is that there are a lot of different ways for a book to happen.

Kyle Beachy: Those feel like extremely wise words, Laura. And Mike I'm interested in your performative approach, and could surely learn from it. But the big obvious difference between writing and making music is that music is made to be heard always, and only very rarely read. So there's gonna be a gap between how a thing we write exists on the page versus how it sounds through a microphone. Maybe part of my anxiety about reading and promoting is I fear it might somehow affect the writing itself, like syntactically. I always think of Blake Butler in this discussion, since his work strikes me as distinctly vocal and cadenced, the sort of writing I badly want to hear. But on the page the experience is totally different. I guess what I'm thinking of is an old distinction, between two forms of entertainment (reading v. listening), and finding them at least partially at odds. I think the slam poetry conversation probably overlaps here, somehow.

Roxane Gay: I don't really enjoy readings and I have a public speaking phobia so the face to face part of being a writer is really hard for me. I do it when I have to and am very pleasant about it but inside, know that I'm dying. But to answer Andrew's question, I don't find self-promotion dirty. We work pretty hard as writers (or don't) but I don't think there's anything wrong with bringing attention to our efforts. I like people knowing about what I do, and reading my writing, and letting me know what they think about my work. That said, I do think all the social networking and self-promotion can get out of hand. It feels like some writers send me an update every single day and that approach does not endear me. You really have to find that fine balance between getting the word out there about what you do and irritating everyone you know. I probably prefer the online promotion because of my speaking phobia. I'm glad the Internet can be my crutch.

Tom McAllister: I'm glad you said it first, Roxane — I'm not a big fan of readings either. I like talking to authors over a couple of beers, I like asking them questions, and I like the concept of being able to hear a great writer perform his/her work, but I often find that I like the theory of a reading much more than the practice. To be blunt, a lot of readings are boring. Whatever the reason — the writer isn't comfortable speaking, the reading is too long or not well-suited to that kind of performance, the room is hot and stifling and uncomfortable, etc. — I find myself struggling to focus, even I when I know I like the book. Maybe this is a negative reflection on my own merits as a listener, but I like to think I give every reader a shot; it's just that somewhere in the middle, I find myself watching the people in the room, or thinking about my own work, or wondering what I'm going to eat after the reading, and then I realized I've missed two pages of a nine page story. And I know I'm not the only one who feels this way. At AWP, I had about a dozen conversations along these lines: people wanted to support the readings, but people also didn't really want to sit through readings. All of which is a long way of saying this: if even writers and serious readers are ambivalent about readings, it's hard to imagine a casual reader caring at all. When I tell my non-reading friends about events like that, they struggle to even pretend they care. To them, it sounds like sitting in a classroom and being lectured.

Holly Goddard Jones: I'd like to clarify, too, that I'm not against readings wholesale, though I agree with Roxane and Tom that attending them isn't always a joy. I've been to some good ones, and I've been to some miserable ones, and if you teach, as I do, there's just the problem of volume. I have to go to a lot of them. But I've had some great experiences touring for the book. Just this weekend, I did a public library reading in Glasgow, Kentucky, and it was wonderful. I got to see my most influential high school English teacher for the first time in almost 13 years, and they'd laid out a spread of baked goods and little sandwiches and things to welcome me. The librarian gave me a gift bag with locally made wooden kitchen utensils, soap, and cheese. How great is that? In the best case scenario, you get to meet great people who make you feel welcome and who remind you that the book has a life outside of your own mind. You just have to brace yourself for the opposite.

Tom McAllister: I would read pretty much anywhere, any time, if they were giving out free cheese and baked goods.

Caitlin Horrocks: Amen, Tom and Roxane, and thanks to everybody for helping me to clarify some of my own thinking about readings and promotion while my book’s release is still a ways out. I genuinely enjoy giving readings, but as an audience member, I’m often one of the people fidgeting and realizing they’ve missed the middle of a story. Just as a few of you commented that the traditional bookstore tour is a convention that isn’t that successful, I feel like the traditional model of a reading is set up for failure as often as success. Some writing has cadences that come alive out loud; some authors are naturally dynamic performers. But then some prose is quiet and dense and suited to slow, private reading; some authors read like they’d much rather be back at the computer and not in front of these strangers. They can be a lot like sitting in a classroom and getting lectured.

At their best, readings are a new way to experience the work, to feel a different kind of connection to the author, but also just to be entertained. And I really appreciate the individual writers and event organizers who help to make sure that happens, whether that involves just a really fantastic delivery, pairing a visitor with a local writer, with a non-writer performer, or providing baked goods!

A friend who’s had two books come out in the past year invited me onto the bill at a couple of his readings. I wasn’t sure I should horn in on his spotlight, so I sort of pooh-poohed his suggestion with the comment that since my book wouldn’t be out for another year, I didn’t have anything to sell. He gave me a look like I was a moron, and he was completely right: I’d been thinking of book promotion so balefully that I’d lost sight of the fact that performing my work and meeting readers shouldn’t actually be about moving product.