|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

How Lucky, She Thought |

|||

|

Love and Theft, 1988 |

|||

|

A Simpler Creature |

|||

|

Spinning Yarns |

|||

|

Billy Lombardo |

|||

|

The Man With Two Arms (excerpt) |

|||

|

Pasha Malla is the author of The Withdrawal Method (stories) and All Our Grandfathers Are Ghosts (poems, sort of). |

|||

|

|

|

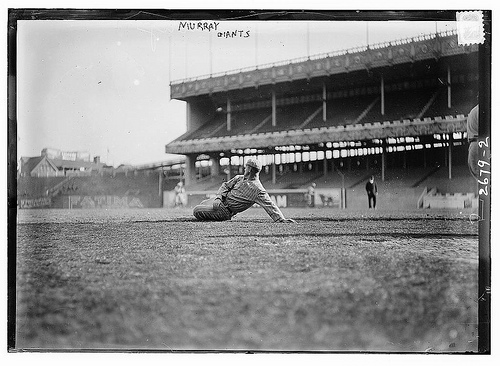

Photo from Library of Congress |

Jane's Addiction, "Been Caught Stealing"

Bear with me here: I don't know shit about baseball. I honestly don't think I could name a single player in the entire professional baseball league, whatever it's called now. I'm vaguely aware of a man named Randy who looks like a NASCAR driver — he might be a pitcher, though he might also be retired — and maybe a certain Rodriguez or Gonzalez who makes a billion dollars a year. Oh, and Derek Jeter. Does Toronto still have a team?

I used to know lots of shit about baseball. In the mid-to-late-80s I could tell you every player's batting average and shoe-size, and craft reasonable hand-drawn facsimiles of each team's logo from memory. I collected pennants and hats and played this weird, secret game in my bedroom with baseball cards and dice that, remarkably, Jim Shepard describes pretty much exactly in his novel, Flights.

Growing up in Canada, I never got involved in "organized" baseball, never wore those tight, stirrupped pants or lounged in the clubhouse with my feet submerged in buckets of ice. My dad was a fierce Marxist who embargoed all Americana — Monopoly, GI Joe, soda pop — as capitalist-imperialist propaganda, and so every summer he signed me up for soccer instead. But free from my dad's socialist tyranny on the school playground, in the morning before class started, every recess, over lunch-hour, and at the end of the day, I played baseball, not soccer. And I loved it.

This was right around the time that heightened regulation of balks came into vogue. Mimicking the majors, our schoolyard games became paralyzed by cries of "Balk! Balk!" every time a pitcher pitched. And, as we were ten year-olds with only a vague understanding of how the world worked, we equated every balk with a walk: if you were at-bat and the pitcher did anything jerky or hesitant, to first base you went. This was especially fortuitous for kids like me, who had neither the skill nor the coordination nor the practice to hit the ball very well. So the balk arrangement was just fine, because the only thing I ever really liked about baseball was stealing bases, anyway.

All my favourite players back then were base-stealers: Vince Coleman, Rickey Henderson, Ozzie Smith, Tim Raines, Barry Bonds. (In the early years of his career Bonds was known as much for his speed on the base-paths as he was for banging homers and being an obnoxious juice-head fuck.) If those guys got to first base it was threatening. Their presence changed the rhythm of the game: pick-off attempts to keep them honest ("Balk! Balk!") only stalled the inevitable and ratcheted up the tension. No matter how many times Vince Coleman was made to tag-up, the second the pitcher went into his wind-up, Coleman bolted, and for a moment, what felt to me (a hyperactive, easily distracted fifth grader, keep in mind) an otherwise listless sport suddenly became a little frantic, and a whole lot more exciting.

I loved the cheek of it, as though the base-runner were breaking a rule the league had forgotten to invent. My family wasn't religious ("the opiate of the masses" was almost as vilified in our house as NFL football), but as a kid I was aware that "Thou shalt not steal" was intrinsic to keeping folks honest and staving off anarchy. So when I stole a base myself, not only was I defying my dad by partaking in the national pastime of the Great Satan, I was also doing something morally suspect as well. Best of all, there was an entire contingent of professionals who'd set a precedent, brazenly flipping a collective middle finger to, in a way, God, and making a multi-million dollar career out of thievery. Everything about it was awesome.

Take Rickey Henderson. Everyone in the stadium — the pitcher, the backcatcher, Rickey's A's teammates, every fan and announcer and popcorn guy — and everyone at home, in their pajamas, sneaking a few innings on TV while their dad was at squash, knew what was coming if he made it to first base. And despite this universal foresight and any attempts to pre-empt the whole thing, Henderson would just go ahead and steal second base (or third!) anyway. Or at least try to — because what thrill would there be in base-stealing without the chance of getting caught? In 1982, Rickey Henderson set still-standing modern-era numbers for bases stolen (130) as well as the most times picked off (42). It's my favourite double-record in any sport, equal parts triumph and failure, the glory made that much sweeter by all that defeat.

After being balked on-base, I borrowed Henderson's lead-off swagger: defiant, taunting, hands dangling between my legs, with all the coiled potential of some cocky jungle cat about to pounce (or so I liked to think). And then, with the pitch, I'd push off and gun it, sliding into second base in a cloud of gravel, with hope against hope I'd avoided the tag. Of course, there wasn't much to it; I don't think I or any of my classmates were ever caught stealing. In fact, so few us could throw the ball with accuracy that attempts to pick off a runner were usually launched into the parking lot, or scooped up by the teacher on yard duty in some misguided attempt at being helpful. As the ball caromed between infield and outfield, and back, and back again, I stole and stole, tearing around the diamond like a criminal breaking for freedom: from second, to third, and finally home, with the ball rattling against the backstop only after I'd high-fived my teammates and taken a celebratory slug of Tab.

Traditionally, baseball has gone in cycles, with an inverse proportion of bases stolen and homeruns hit. Homeruns never excited me; they still don't. What's fun about banging the ball out of play, and then rounding the bases at your own speed, without any urgency or prospect of being stopped? Compared to the drama of base-stealing, a homerun is anticlimactic, even boring. And so, in the 90s, as Barry Bonds muscled up and became less of a base stealer and more of a slugger, and the entire game started changing, my interest in the sport began to wane.

And so I've given up on baseball, pretty much entirely, with one exception. You don't need 18 players to steal bases; in fact, you didn't need a diamond, or even a bat. In parks, on lawns, in backyards and at the beach, get a couple of buddies together and drop a pair of book-bags 30 feet apart. Put a pal on each "base," give them gloves, position yourself between them as the runner, and try to steal. I've always called this game "run-downs," though I guess there are probably other names for it. It's to baseball as target practice is to war — but that doesn't make it any less fun.

So, to celebrate Opening Day on April 5th, when I'll be back in my hometown visiting old school friends over Easter, this is what I'll be dragging them out to do. I've had a hankering for something like this lately, what with my obedient, theft-free life. I haven't stolen anything in a long time: I sweat too much to be a very good shoplifter, and downloading pirated music doesn't count. Maybe a little base-stealing is just the sort of thing I need to get me back on track — feeling a bit more human, for one thing, but also, with any luck, rekindling my love for the game of baseball, too.