|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Are You Lonesome Tonight? |

|||

|

Space is Our Future |

|||

|

The Weirdest Thing |

|||

|

Sunsets Unlimited |

|||

|

489 Points |

|||

|

Rain Escape |

|||

|

They Shared an Egg |

|||

|

First Book Roundtable Discussion |

|||

|

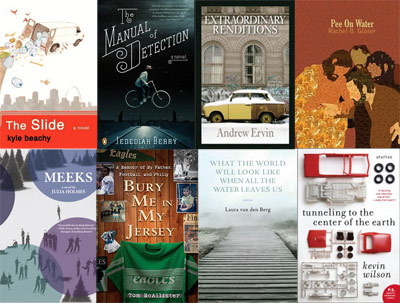

Kyle Beachy is the author of The Slide (The Dial Press, 2009). He lives in Chicago and teaches writing and literature at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Univeristy of Chicago's Graham School, and Roosevelt University. His short stories and essays have or will appear in St. Louis Magazine, Another Chicago Magazine, as a Featherproof Mini-Book, and elsewhere. |

|||

|

Jedediah Berry's novel The Manual of Detection (Penguin, 2009) won the William L. Crawford Award and the Dashiell Hammett Prize, and is a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Award. His short stories have appeared in journals and anthologies including Conjunctions, Chicago Review, Best New American Voices, and Best American Fantasy. He is an editor at Small Beer Press. |

|||

|

Andrew Ervin's first book, a collection of novellas titled Extraordinary Renditions, will be published by Coffee House Press in September. His fiction has appeared in Conjunctions, Fiction International, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Louisiana, but that is about to change. |

|||

|

Roxane Gay's first collection, Ayiti, will be released in the Fall of 2010 (Artistically Declined Press). Other work appears or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, DIAGRAM, McSweeney's (online), Gargoyle, Annalemma and others. She is an assistant professor of English at Eastern Illinois University and co-editor of PANK. Find her online at www.roxanegay.com. |

|||

|

Rachel B. Glaser is the author of Pee On Water (Publishing Genius Press 2010). Her stories have appeared in 3rd Bed, New York Tyrant, Unsaid and others. She currently lives in Easthampton, MA with the author John Maradik. |

|||

|

Julia Holmes was born in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and grew up in the Middle East, Texas, and New York. She is a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA program in fiction, and lives in Brooklyn. Her first novel, Meeks, will be published by Small Beer Press in July. |

|||

|

Caitlin Horrocks is author of the story collection This Is Not Your City (Sarabande 2011). Her stories appear in The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories 2009, The Pushcart Prize XXXV, The Paris Review and elsewhere, and have won awards including the Plimpton Prize. She lives in Grand Rapids MI, where she is an assistant professor at Grand Valley State University. |

|||

|

Holly Goddard Jones is the author of Girl Trouble, a collection of short stories. She teaches at UNC-Greensboro. |

|||

|

Tom McAllister's first book Bury Me in My Jersey: A Memoir of My Father, Football, And Philly (Villard/Random House) was released in May 2010. His shorter work has appeared in several publications, including Black Warrior Review, Barrelhouse, and Storyglossia. A 2006 graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he is currently a Lecturer in the English Department at Temple University in Philadelphia. |

|||

|

Laura van den Berg was raised in Florida and earned her MFA at Emerson College. Her fiction has appeared in One Story, American Short Fiction, Conjunctions, Best American Nonrequired Reading 2008, Best New American Voices 2010, and The Pushcart Prize XXIV, among others. Laura’s first collection of stories, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us (Dzanc Books, October 2009), was selected for the Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Program and long-listed for both The Story Prize and the Frank O’Connor Award. She was the 2009-2010 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College and is the recipient of the 2010-2011 Tickner Fellowship at the Gilman School. |

|||

|

Kevin Wilson is the author of the story collection Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (Ecco/Harper Perennial, 2009). His fiction has appeared in Tin House, One Story, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. He lives in Sewanee, TN. |

|||

|

Mike Young is the author of We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough (Publishing Genius Press 2010), a book of poems, and Look! Look! Feathers (Word Riot Press 2010), a book of stories. Recent work appears in American Short Fiction, LIT, and Washington Square. He co-edits NOÖ Journal and Magic Helicopter Press. He lives in Northampton, MA. |

|||

"BEGINNINGS"

|

|

(PREV: Introductions)

For those of you with story collections, did you find much resistance from the publishing world? Is what they say true? Are story collections difficult to sell? Actually, let's open that up to the whole group. Julia, you're with Small Beer, which has a pretty distinct aesthetic, it feels like (feel free to correct me). Did you find any resistance to Meeks as you were sending it out? Kyle, your novel The Slide, which I loved a lot, does not feature the Brothers of Mercy, but does none the less reach a pretty great level of strangeness at times. Did you have any resistance to the book as you were sending it around for these reasons? What about the rest of you? Any war stories from the front lines of first book publishing?

Roxane Gay: I can't say I've encountered much resistance because I haven't submitted my manuscripts very much this year on account of trying to finish my dissertation. Of all the manuscripts I have lying in wait, this is the last one I expected to be picked up so quickly and I'm still not entirely convinced a book is going to happen because it feels so surreal. I did send it to a few places and there was some resistance — too ethnic, too grounded in realism, too this, too that, we no longer publish fiction, etc., but I didn't feel any specific resistance to the idea of a short story collection or I tuned that resistance out because I love short story collections and I'm stubborn. That said, my full length short story collection which I am "shopping" around is certainly meeting with resistance if by resistance you mean constant, soul destroying rejection. I call it resistance training. It builds muscle.

Mike Young: I sent a manuscript to Jackie Corley at Word Riot Press in September 2008. In December 2009, she sent me an email back saying she wanted to publish it, which was terrific. The manuscript had changed considerably since then. In fact, there was a new manuscript, with only a couple stories from the original. To make things even more exciting, my new manuscript wasn't exactly "done." So I asked Jackie if I could send her the new manuscript to look over (I should've asked this paragraph if it was okay to use the word manuscript so many times) when I finished it. She said sure, then she contacted me via Gmail Chat the next day or something and said "hey mike, i'm confident in your writing style so let's just say that we're officially pubbing your book and you're just delivering the revised final manuscript to me in jan." Of course, I didn't end up delivering her a final until April.

Holly Goddard Jones: Selling my book took about two years. I got an agent right out of graduate school, before I was really ready for one, and that was part of the problem. And this agent, who was older and very established, just wasn’t the right fit for me. I don’t think that she was used to hand-holding a young, insecure writer, and I wasn’t mature enough to be my own cheerleader. I also tried in those two years to write a novel, and I got about 100 terrible pages in before I realized that I was going to have to toss it. That, I think, is the biggest pressure on the writer with a book of short stories: to produce a novel, or an idea for a novel that’s so great that a publisher will take your stories on the promise of that other project. Anyway, it’s a long story, but now I’m with a different agent, and—for good or ill—my editor bought just the stories, not the stories as part of a two-book deal. Of course it would be nice to have the security of a contract for the novel, but the good thing, I guess, is that I didn’t have to force a second project that I didn’t believe in to sell the first project that I did believe in.

Laura van den Berg: I had a pretty lucky, low-resistance experience with my collection. In 2007, after winning the Dzanc Prize for a work-in-progress, they asked to see the rest of my collection and made an offer shortly thereafter. In the meantime, I had been taken on by a great agent, who has been an invaluable part of the process. Like Holly, I sold just the stories, for better or worse, even though I had, at the time, started the novel I’m now revising; the 2-book system seems to work beautifully for a lot of people, but I was a little freaked out by the notion of committing contractually to write a novel when the project was still in its early stages, and fortunately Dzanc was wonderful about doing the stories alone.

Kyle Beachy: There were certainly times during my stretch of rejections that I found comfort in some analogue of that notion, strangeness. Mostly I tried to drop my head and reduce the process to a numbers game: there are this many agents and I can send out this many query emails and all of this rejection is technically part of what it means to publish, and so on. But I was never immune to the soulcrush, nor rationalizing my way out of it. It's extremely easy to bemoan the tastes of others. Circumstances, too – I remember a few particularly sad moments when I frankly and truly blamed Zach Braff. But of course there are a thousand reasons a publisher or agent won't stand behind a manuscript, and rarely does strangeness cover them. The truer issue was that my book still needed a lot, lot of work, and I had to find both an agent and editor who were up for it. And I think that even at my darkest moments I recognized how strange was too easy an explanation. It's the same self-service we get from experimental, sometimes, or avant-garde, these kind of therapeutic jumpsuits we zip ourselves safely inside then refuse to take off and launder, even after we've sweated through and the stench has turned rank.

Tom McAllister: I don't have a story collection, or enough good stories to comprise a readable collection, but I'll chime in here re: war stories, I've been fortunate not to have much difficulty on that front. The greatest frustration was waiting about 21 months for the book to finally come out — about 2 months longer than it took me to actually write the thing. They wanted to market it as a Father's Day gift, and when I signed the deal in mid-September of '08, they said we didn't have quite enough time to release it by '09... although one could argue that if 9 months is enough time to conceive and gestate a human child, then maybe it ought to be enough time to put a cover on a book and print it, but I know I'm oversimplifying things. But definitely for me the most frustrating thing about this whole business is the glacial pace at which it moves. I'm an impatient guy — the primary reason I queried my eventual agent is because no one else had responded after several months and I read somewhere that she gives quick rejections via email. I just wanted someone to acknowledge that my query existed, I guess.

Caitlin Horrocks: When I finished the first version of my collection I'd absorbed the conventional wisdom that story collections on their own (no novel) were an impossible sell, and that my best and only chance at publication was to enter the manuscript in contests. So I did, and won one, and then seven or eight months later things went south. By that time I had an agent, and she sent the collection around to some places. I was expecting 'no's, and got them, but what made the process difficult was that most of the rejections weren't "not right for me" or "not my thing." Editors liked the stories, sometimes really, really liked them, but we always circled back to the problem that my story collection was a story collection. I had a synopsis for a novel that my agent sent with the stories, and everybody agreed that that book sounded pretty great. Unfortunately, I hadn't written it yet. Happily, Sarabande embraced the collection with open arms. Overall, I ended up feeling that the resistance to short story collections was both very real and overstated. It was a problem, to have a book of unlinked stories with no novel waiting in the wings, but I got fair reads and more encouragement than I'd expected. I wasn't laughed out of town, which is somehow what I'd thought happened to short story writers.

Laura van den Berg: Not to stray too far from the question at hand, but Caitlin I totally agree with your feeling that the resistance to collections is both "very real and overstated." The resistance is a real thing to be sure, but there's also support for the story out there. After all, each year collections get published by houses big and small, win awards, get reviewed, etc. I'm not totally convinced that story writers have it that much harder than everyone else.

Caitlin: Laura, totally agreed. And it seems like one thing guaranteed not to help short story collections is for all the people who write and read and like and buy them to talk constantly about how no one else reads or likes or buys them.

Kevin Wilson: The collection wasn't difficult to sell, as long as I also had the promise of a novel. Ecco, I don't think, would have taken the collection if I didn't have 100 pages of a novel to attach to the deal. It was like this for most of the other publishers. They liked the stories, but wanted a novel to go with it.

Andrew Ervin: The idea of how to label a book is a tricky one. And by "tricky" I mean "market-driven." It wasn't Moby-Dick: A Novel or Leaves of Grass: Poems, right? My three novellas sold because combined they sort of resemble a novel. The publisher refuses to put "three novellas" on the cover; that's a bit of a disappointment, but I also completely trust my editor and now that he's doing what he thinks is best to get the book in most peoples' hands.

Rachel B. Glaser: I was blindly, amateurly, boldly sending my collection around. It was exciting anytime I could send it to a familiar name and say something that pretended that I was connected to the editor in some way. Then, brilliant Mike Young suggested I send it off to Adam Robinson (of Publishing Genius) who had written online that he had enjoyed some of my poems. So, in that way I luckily avoided the prejudice against stories collections, that I've heard so much about.

Julia Holmes: Meeks went out to 25 or 30 publishers over a two-year period — some of the rejections were thoughtful, even helpful, but a lot of them cited the "problem of strangeness" in one way or another. I'd sort of expected that, and I started to notice that, from opposite sides of some writer/publisher divide, we were all treating "strangeness" as a self-evident problem. That seems like a bad habit, and I agree that it's an easy expectation to get caught up in — and, of course, it's true that strangeness can be shorthand for all kinds of things. But I feel like whatever resistance existed closed certain doors and ultimately pushed the book in the right direction, and it ended up with exactly the right publisher and editor. I don't have the benefit of a big-house experience (for comparison), but in the case of Meeks, I think having the chance to work with a smaller press was a huge advantage.

(NEXT: Following the path from sale to publication, and the process of editing)