|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Are You Lonesome Tonight? |

|||

|

Space is Our Future |

|||

|

The Weirdest Thing |

|||

|

Sunsets Unlimited |

|||

|

489 Points |

|||

|

Rain Escape |

|||

|

They Shared an Egg |

|||

|

First Book Roundtable Discussion |

|||

|

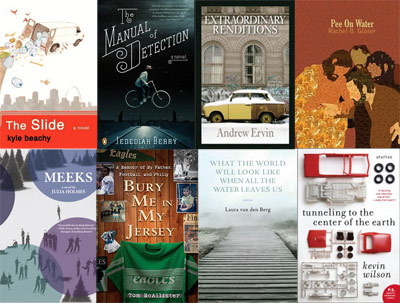

Kyle Beachy is the author of The Slide (The Dial Press, 2009). He lives in Chicago and teaches writing and literature at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Univeristy of Chicago's Graham School, and Roosevelt University. His short stories and essays have or will appear in St. Louis Magazine, Another Chicago Magazine, as a Featherproof Mini-Book, and elsewhere. |

|||

|

Jedediah Berry's novel The Manual of Detection (Penguin, 2009) won the William L. Crawford Award and the Dashiell Hammett Prize, and is a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Award. His short stories have appeared in journals and anthologies including Conjunctions, Chicago Review, Best New American Voices, and Best American Fantasy. He is an editor at Small Beer Press. |

|||

|

Andrew Ervin's first book, a collection of novellas titled Extraordinary Renditions, will be published by Coffee House Press in September. His fiction has appeared in Conjunctions, Fiction International, The Southern Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Louisiana, but that is about to change. |

|||

|

Roxane Gay's first collection, Ayiti, will be released in the Fall of 2010 (Artistically Declined Press). Other work appears or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, DIAGRAM, McSweeney's (online), Gargoyle, Annalemma and others. She is an assistant professor of English at Eastern Illinois University and co-editor of PANK. Find her online at www.roxanegay.com. |

|||

|

Rachel B. Glaser is the author of Pee On Water (Publishing Genius Press 2010). Her stories have appeared in 3rd Bed, New York Tyrant, Unsaid and others. She currently lives in Easthampton, MA with the author John Maradik. |

|||

|

Julia Holmes was born in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and grew up in the Middle East, Texas, and New York. She is a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA program in fiction, and lives in Brooklyn. Her first novel, Meeks, will be published by Small Beer Press in July. |

|||

|

Caitlin Horrocks is author of the story collection This Is Not Your City (Sarabande 2011). Her stories appear in The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories 2009, The Pushcart Prize XXXV, The Paris Review and elsewhere, and have won awards including the Plimpton Prize. She lives in Grand Rapids MI, where she is an assistant professor at Grand Valley State University. |

|||

|

Holly Goddard Jones is the author of Girl Trouble, a collection of short stories. She teaches at UNC-Greensboro. |

|||

|

Tom McAllister's first book Bury Me in My Jersey: A Memoir of My Father, Football, And Philly (Villard/Random House) was released in May 2010. His shorter work has appeared in several publications, including Black Warrior Review, Barrelhouse, and Storyglossia. A 2006 graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he is currently a Lecturer in the English Department at Temple University in Philadelphia. |

|||

|

Laura van den Berg was raised in Florida and earned her MFA at Emerson College. Her fiction has appeared in One Story, American Short Fiction, Conjunctions, Best American Nonrequired Reading 2008, Best New American Voices 2010, and The Pushcart Prize XXIV, among others. Laura’s first collection of stories, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us (Dzanc Books, October 2009), was selected for the Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Program and long-listed for both The Story Prize and the Frank O’Connor Award. She was the 2009-2010 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College and is the recipient of the 2010-2011 Tickner Fellowship at the Gilman School. |

|||

|

Kevin Wilson is the author of the story collection Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (Ecco/Harper Perennial, 2009). His fiction has appeared in Tin House, One Story, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. He lives in Sewanee, TN. |

|||

|

Mike Young is the author of We Are All Good If They Try Hard Enough (Publishing Genius Press 2010), a book of poems, and Look! Look! Feathers (Word Riot Press 2010), a book of stories. Recent work appears in American Short Fiction, LIT, and Washington Square. He co-edits NOÖ Journal and Magic Helicopter Press. He lives in Northampton, MA. |

|||

"BEGINNINGS"

|

|

(PREV: Story collections v. novels, and "strange" books)

Have you others experienced a similar pace from sale to publication? My guess is there's no across the board answer, but I'm curious about how many of you found things to be like Tom did.

Holly Goddard Jones: It took about a year from contract to release for me, which seemed like a good amount of time. I wouldn't have wanted it to be faster. In fact, now that the book is out, I have to say — sorry, Tom! — that I enjoyed anticipating the book's release more than I've enjoyed having it out in the world.

Jedediah Berry: I spoke with several agents about my novel before signing with one of them. It was a process I took a good deal of care with, because the manuscript wasn't finished (this was during my last year of grad school), and I knew my agent would be among the few people who were reading and providing feedback on the novel as I completed it. I feel I lucked out here, because the agent I went with understood what I was up to, and he's a great editor. Then he found an excellent editor for the book. So, no real battle scars to show off. Writing, and rewriting, and rewriting: that was the hard part.

Kyle Beachy: I'm with Jed (may I?) here — though I'm curious how your interactions with your editor played out. Was there a good deal of back and forth once he / she bought it? I know the first thing my (young and very smart) editor sent me was a ten-page, single-spaced memo about the book, which made clear both how well he understood what I was trying to do and how much he believed remained to get done. I recall my stomach plummeting. Of course now I'm grateful he put so much time into my revisions... the book needed them.

Jedediah Berry: You may, Kyle, and yes, that sounds familiar. I think we did four rounds of edits on the book, and much of it was substantial: there are three completely different versions of the penultimate chapter now moldering on the trash heap. But the most important thing my editor did was to point out when something didn't make sense to him: when he lost sight of a character's motivation, or when some aspect of the story didn't add up. He asked important questions, and they were questions the book needed to have answers for.

Kyle, you and Jed seem to have had similar experiences as far as feedback from agents and editors throughout the editing and revisions process (others, please join in here too). I'm curious about how it works. Notes from editors and rewrites, rewrites, more rewrites. We've talked a little already about the time between sale and publication. So, what happens, exactly, during that time? Frantic re-writes and much nail-biting or are we talking martinis by the pool and regular ego stroking calls from an editor?

Tom McAllister: For me, there wasn't much re-writing. My agent had me work up one chapter she didn't think was so great, but that was it. My editor had some suggestions, most of which were quite helpful, and some of which were terrifying (i.e. "I think you should maybe cut all of the Iowa stuff," which, at that time, was 25% of the book, and which ultimately I didn't do), but he only had me do two re-writes, neither too drastic. One benefit of the very long waiting period was that I had generous deadlines on the re-writes, which was nice. Anyway, outside of the editing, I'd say I spent maybe 13 of the 21 months doing nothing related to the book; I just started working on the next book. I heard from the editor maybe every 6 weeks, usually just him checking in to reassure me that my book still existed; I think he could sense my impatience, so he tried to placate me now and then.

Tom McAllister: Oh, forgot to add (sorry, I know my answers are getting long), in the remaining 8 months, I found myself doing a lot of semi-tedious stuff. Reading the galleys enough times that I don't think I'll ever want to read this book again, begging people for blurbs, getting permissions to quote and use names, talking to the legal dept. (favorite question: "In chapter 4, you say your Uncle Mike is a loser. Can we find some way to prove that?"). The most fun part for me was having some input on the cover and seeing it come to fruition — giving the book a cover seemed to legitimize it.

Laura van den Berg: Well, there were martinis, but they weren’t served poolside. Rather it was my own recipe, severed in giant water glasses. But back to writing! I worked on the stories with my agent and then my publisher had some light notes. I also had a good amount of time between the acceptance of the collection and having to turn in the final manuscript, so I read and re-read the stories and then revised and revised. For some of the stories, I completely re-wrote them and there was one in particular that I just couldn’t get to work and was certain I'd have to drop from the book. But I re-wrote and re-wrote and then, at the final hour, something finally clicked. Once the manuscript was turned in and we’d gone through the production process (helping with the cover was super fun!), the promotion process began, which is an adventure unto itself.

Kyle Beachy: I realize this exchange isn't geared toward a focus on this distinction, but I wonder if people agree that one key difference between the major and the independent publishers is the fact of having a dedicated editor? Do people agree that smaller presses are less likely to nudge a manuscript one way or another? I'm wondering if the sense I'm getting here is generally true...Laura, your phrase "light notes" strikes me as particularly hands offish.

Holly Goddard Jones: Working with my editor at Harper, Sally, was absolutely the best part of the experience. I thought that she was a perfect reader, one of the best I've ever had — thoughtful, wise — and she asked all of the right questions, so that I could revise in a way that still felt very personal. I never felt steered into a vision that wasn't mine, but I felt at every turn that I'd put the book into the hands of a person who really loved it and wanted it to be the best version of what I could produce. I know that I was very, very lucky to have her, and I say all of that because I think the belief about small presses versus New York presses (one I harbored) is that a NYC press will never provide that level of care, especially to a no-name writer of short stories. Perhaps my situation was anomalous, but that aspect of getting a book into the world was just about ideal.

Kevin Wilson: I'd gone through a lot of edits with the editors who published the stories in journals. Then I had a long back and forth with my agent (who I think is an incredible editor and we work really well together). Once it got to the publisher, there weren't many changes made. On one story, we changed the gender of the narrator. That was it. I felt the editor was reading it very closely, and we had many discussions about it, but I also felt like I had spent so much time with the stories, that it was hopefully already in a good place.

Laura van den Berg: I had a similar experience as Kevin, in that I had done lots of edits on the stories with magazine editors (after the title story was accepted, for example, I probably did 6 or 7 drafts with that editor) and then edits on the entire manuscript with my agent (a great reader and editor), looking at everything from revising individual stories to what to drop/add to the way the stories should be ordered. By the time the manuscript reached Dzanc, they felt it was in pretty good shape, so the lack of an intensive editing process didn’t feel so much “hands off” as an expression of that sentiment. However, I, nervous wreck that I was, kept editing until the final hour.

Kyle, to go back to your question, I do think it’s true that at indie presses, the staff are usually wearing multiple hats, so you might be less likely to find someone whose job is exclusively editing. On the other hand, I have talked to friends who published with indies—Graywolf, Coffee House, Sarabande—that had intensive editing processes, so I would imagine it’s a case-by-case thing with both the author and the publisher more than anything else.

Jedediah Berry: By day I'm an editor with Small Beer Press, and I can say that I work closely with my authors on the editing of their manuscripts. It's true that I also act as publicist and events coordinator, and I do layout and design, but then everyone at the press does some of all those things, so the ideas are always circulating and being built upon. If anything, I was worried that I wouldn't receive that same kind of attention when I went with a big press for my own novel. As it turns out, I learned a lot about editing from my editor at Penguin, and have been able to put some of those lessons into practice at Small Beer.

Tom McAllister: Kevin (and others, of course), I'm curious to hear more about the "many discussions" you had with your editor. You didn't make too many changes, but apparently spent some time negotiating over the lack of changes; was any of that contentious? How did you go about vetoing suggested changes? Was your editor receptive to your ideas, or did you really have to fight for your work?

Kevin Wilson: Hey, Tom, the discussions were mostly about making sure that I was happy with the final product, since it was my last chance to make any changes to the text. We also talked a lot about the collection as a whole, where to put stories, how one might rub up against another in a more pleasing way than a different story. So, I think our discussions were more about the larger identity of the collection and not on specific stories. It was not a contentious process at all. Part of that was because, in the beginning of the process, I was so happy to be published, that I would have accepted just about any changes as long as I got my picture on the back of the book, but I got over that quick. Mostly the process was easy because I got along with my editor and neither one of us is a person to dig in our heels on a specific issue and we were working hard to understand our sometimes opposing positions on certain stories. We just talked about what I wanted to do with the stories, what she then thought they were actually doing, and how to make everything line up. I think I'm not answering this well because we also spent a lot of time talking about babies, because we were both close to having a first child. We also talked about hamburgers and which ones we wanted to eat and which ones we did not when I eventually came to visit her in New York.

Andrew Ervin: It's fascinating to hear how other editors work, thank you all. (Almost two years in Louisiana and I still find the word "y'all" repulsive, yet am perfectly content with my native-Philadelphian "youse." But nevermind.) My agent made some amazing suggestions and then I asked my editor to get angry with my ms. and edit the bejesus out of it. He went easy on it, though, and I learned a great deal from his insights and those of the proofreader. At a certain point, like Tom, I was unable to read it anymore with any clarity. I'm hoping for a second wind before I have to go out and do readings and try to make people excited about spending their sixteen bucks.

Roxane Gay: My editor has given me some great suggestions on my manuscript but I think I'm more brutal with the editorial suggestions than he is because I am so nervous about putting this book into the world.

We can actually get some feedback from both editor and author. Jed, you and Julia have been working together on Meeks, right? What's the editorial process been like from the other side of the table, so to speak? And, Julia, have you found that your experiences so far have matched up with what's been said?

Julia Holmes: I think they do match up for the most part — it's been a great experience (with lots of rewriting). I have to say, working with Jed has been fantastic. It's hard not to go into an editorial relationship with a certain amount of anxiety — who is the person, how does s/he think about things? Early on, we talked sort of broadly about the structure of the book, how to handle the transitions between narrative voices (there are a few in the book), and that conversation put me entirely at ease. After that, it seems to me that we went through three or four rounds of revisions (over 9 or 10 months, maybe), all pretty major, in the sense that the structure of the book changed each time, whole narratives came and went. But the questions Jed asked really transformed the book — seemingly innocent (or maybe I mean lucid/ straightforward) questions about how the book, or the world of the book worked. And then I'd go off to start rewriting, and I'd realize they were incredibly complicated questions. They went to the heart of the matter, and they were hard to answer, but restructuring the book around them made all the difference — and they also showed how deeply he was thinking about the book on its own terms, which meant a great deal. And because I trusted his judgment, I was comfortable going in and yanking out parts of the book that had been there so long I'd started mistaking them for vital organs. But maybe the aspect of the process that surprised me most was the encouragement to experiment more (not less) as the process went on, and it was liberating to take chances, try things out, even close to the deadline. I think you have to have an abiding faith in someone's judgment to do that. I always felt like we were both thinking about the book in similar ways, generally interested in the same kinds of problems — though maybe a great editor makes the process feel collaborative in that way. Sometimes I felt like we were fellow engineers on a weird malfunctioning rig in the North Sea — but in the most pleasant sense. Anyway, for my part, I feel incredibly lucky things worked out as they did — it's been a pretty ideal first-book experience in that regard.

Jedediah Berry: To stick with that image of a pair of engineers, which I love: I tried to be the fellow crouched over the tool bag, handing up wrenches and hammers as needed, and maybe at most saying things like, "What you need now is one of these right here" or "Just a little further to the left." In other words, I wanted to make use of my experiences while keeping my particular writerly inclinations out of the equation as much as possible. I fell in love with Julia's book because I was completely convinced of her vision. I felt it was my job to help her achieve that vision as fully as possible—to get things moving, and then to get out of the way. It was an exciting process, and I'm very proud of the results.