|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

How to Kill |

|||

|

Ma Vie En Rose: My Life Wrapped in Cellophane |

|||

|

Libertyland |

|||

|

Brass on Oak; Oak on Marble; Marble on Glass; Glass on Steel |

|||

|

Chorale for the First Rental House on Your Block |

|||

|

Mattox Roesch |

|||

|

Ingrid Burrington |

|||

|

Craig Davis Is from Topeka, Kansas. His stories have recently appeared in or are forthcoming from The Southeast Review, Monkeybicycle, The New York Tyrant, Fifty-Two Stories and elsewhere. He lives in Kansas City. More information can be found at www.craig-davis.com. |

|||

|

|

|

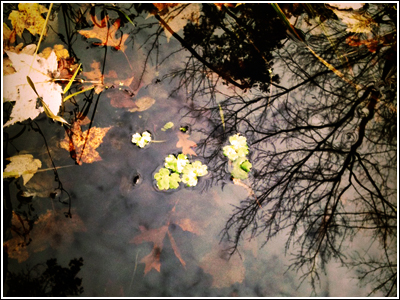

Photo by Ryan Molloy |

Outside on his porch was an indoor sofa. But he kept the lawn mowed. Early in the morning when the grass was still too wet — there he was, limping behind the mower, cursing God and us when it clogged. His curses, above the buzz of a lawnmower... one summer we woke to this.

A neighborhood of bungalows and ramshackle ranches. Split level custody. Dent fenders. Once this was a suburb. Once this was all brand new. Now this newly-minted man, a boy banged up a bit. Skin already piled around his eyes, throw rugs in a yard sale. He was about the age of our oldest cousins, but unfamiliar. He was there that summer suddenly, like a new kind of normal, a kind which waited. A warning sign.

He was there to learn. He learned to cut the grass before the heat slipped into the day. He learned the dandelion dust. He learned to like naps on the porch. He learned our names. If you asked him, he said his name was whatever you said yours was. At first we didn't believe him. When we told our moms that he'd given us a band-aid for our skinned knee or pulled a splinter out of our thumb, they asked who did, now? But they were always sneaking side looks at his house. Through the blinds they watched him and our stepdads watched our moms and we left our toys in his yard for him to mow over.

Was he teaching, too? We learned also after all. We learned he would not pick up a wiffleball in the path of a lawnmower. We learned that grown-ups could not chorus as we could. Could not talk all together until the meaning came forth from the noise like a face in the static. He didn't care for our noise, our nosiness. We knew that. But he also didn't care about it. He did not heed. With his whiskey and evening air. Because if no one knew him, then he wasn't even there. We learned there were no mysteries, really. He did, too.

Just before he left, together we all learned to leave it alone.

The bigger kids who played basketball in the street — the ones who won't move out of the way for traffic — they tipped their chins up at him whenever he came out onto the lawn, ushering his part-beagle onto the grass. If we asked to pet his dog, he made sure to remain in plain sight. He never let us in his house.

He sat on the porchcouch and tipped back golden cans of beer. Little runs of condensation dribbled down onto his shirt and dyed it darker. He got drunk, but not dad-drunk. He never yelled at the TV. Or threw a beercan at a car that passed too fast. He did watch them — the cars, the little ones — rolling the stop sign on Chasey at Woodson. The ghost of a ponytail in the driver's side window. He knew every red car in the city. We all know why. A ghost, a ponytail, a cast of light like a lure, a ghost, a ponytail.

It was hard for us to imagine — then — an entire day without a bike ride or a ball to toss or a new cussword to practice. It was impossible to imagine a world of letting the screen door slam in the silence after lunch. Of not speaking for a stretch of days. We could only picture him stepping inside to nap, or pitch pennies into the garbage disposal, or read the postcards the mailman handed to him all the time. It was easy to imagine these cards were from his grandma for his birthday or because his cousin was on vacation in Texas. We got those kind of postcards. But every couple days? Who could imagine that? Who could imagine this man was not our neighbor at all, but a maccabee of many summers that rested, waited? Who could imagine a couch on every porch, on every block? A whole neighborhood where no one knows what the fuck is a divan? Who could imagine the ease with which we can now answer these questions? Imagine scribbling a question on the chalkboard and never coming back from recess. Imagine mailing yourself postcards and throwing them into the wind for anyone to read.

He sat out there late, slapping bugs with his porchlight off. He ran his hand through the tangle of Spanish question marks on his head. He laughed out loud alone. We waited — though we didn't know it — for the fall. Burn the leaves.

He learned to leave. We yearned. Young. None of us knew why.