|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Keeper |

|||

|

Antoine is Not Here |

|||

|

Like That Thing Only Different |

|||

|

Russians |

|||

|

|||

|

Grace Krilanovich |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

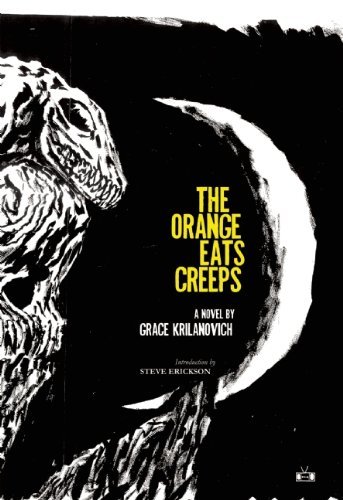

One of the things that initially got me excited about The Orange Eats Creeps, before I had any notion of what it actually would be, was the incredible list of “inspirations” you compiled in an interview with the book’s publisher, Two Dollar Radio, which was like a greatest hits collection from my own library, circa 1996 – 2004:

-

Andy Warhol’s Trash, Naked Lunch…Creepy Victoriana: Wisconsin Death Trip…The Diary of Laura Palmer…the art of Joe Coleman, Journey to the End of the Night, the music documentary “The Decline of Western Civilization”…the Amok Fifth Dispatch [!]…the RE/Search books, especially stuff about JG Ballard and Burroughs and cut-ups…

Actually, your list is much more extensive and includes a number of other things that also immediately rang bells for me. I had a sense reading that interview that you were describing the pieces of something like my perfect novel. Which The Orange Eats Creeps is pretty close to being, but in an entirely unexpected way. “Trash” or “sleaze” culture exists courtesy of a kind of excess, a peculiarly American—maybe even peculiarly Southern Californian—style of pastiche, where the sole criterion for appropriateness is perceived popular success; if a movie about teenagers is popular, and Michael Landon is popular, and a movie about a werewolf is popular, why not Michael Landon in “I Was a Teenage Werewolf?” The book flirts with this arch mode pretty blatantly at the beginning (constructions like “mechanical teen felon meathead,” or that great epithet, “Slutty Teenage Hobo Vampire Junkies”), but I also see a kind of analogue to it underlying the narrator’s beautiful, rather surprising way of ordering thoughts and depicting scenes. Perhaps you could tell us a little bit about how you see those inspirations playing into the conception and writing of The Orange Eats Creeps?

Interesting you mention Southern California, because I hadn’t thought of that but it rings true. I’m a rare north-to-south CA transplant. Los Angeles appeals to me, even as it grosses me out. The LA punk scene really played around with the trappings of Hollywood and the detritus of the first half of the 20th century, more than any other. I’m thinking of those great shots of John and Exene’s apartment in Decline—with all of its salvaged and cast off items, religious paraphernalia, wind-up skulls, tiger figurines made of real fur, folk Americana-garbage (I’m sure they literally dug some of that stuff out of the trash). In The Unheard Music John Doe goes on to explain how they salvaged an “X” off a soon-to-be-demolished Ex-Lax factory. Exene alone managed to incorporate Gloria Swanson’s makeup, Donna Reed’s apron, a Kentucky mountain girl’s wail, and neo-beat/post-Manson poetry into one quintessentially LA pomo mish-mash. Other LA punkers who reveled in the junk pop excess of the SoCal landscape… right off the top of my head I would say Alice Bag, Geza X, Boyd Rice, The Cramps, Redd Kross, Flesh Eaters... I think there was a particular West Coast delight taken in putting things together that wouldn’t (shouldn’t) normally be put together. A culture of new combos that was absent in a more high-stakes NY art, literary and music environment. This has been talked about a lot already… Nobody cares about LA! As far as I can tell, from what I’ve heard, nobody with any clout was watching or attaching too much significance to what was going on here, and that allowed for all sorts of odd-balls and wing-nuts—art movements of one—to do their thing, from the Pacific Northwest on down to La Jolla. SF definitely breaking new ground of weirdness.

I guess I knew early on that my own project of sifting through the assorted colorful shiny objects in front of me would be mirrored by my characters, and maybe like you said, echoed in the formal aspects of the writing itself. Anybody who’s been to my apartment will tell you that I am kind of a pack rat, that I’ve more or less surrounded myself with so many objects that my pad looks like a cluttered media cave (books and records) with every available surface laden with objects that captivate and amuse me: a 1910’s celluloid cross, a skeleton key, a disco-mirrored owl, a doll house fireplace, braided dried sweet grass, antique handwritten recipes, diaries and letters, crystals, etc.

Play is very important to this process. I would even say the most important. I think anytime you can create that moment of discovery, of unknowing, unplanned discordant undefined play, you’re on to something. I have little boxes filled with stuff that I occasionally dig through – but not so often that I remember what’s in them. One, for example, has a few of these little psychological test booklets in it—old ones from the ‘30s—and doll furniture, a framed photo of my childhood cat, baby teeth, and so on. So I’ll go in there and dig. It fills your head, y’know, and then it’s fun to go to the page with that.

Such glorious junk in Southern California! It should be celebrated: it is unique, in my experience. The swap meets and thrift stores there are so much more impressive than anywhere else in the U.S. Our answer to Paris’s Puces. Speaking of, your collection reminds me of something that William S. Burroughs said was in his Paris Review interview:

-

Cutups make explicit a psycho-sensory process that is going on all the time anyway. Somebody is reading a newspaper, and his eye follows the column in the proper Aristotelian manner, one idea and sentence at a time. But subliminally he is reading the columns on either side and is aware of the person sitting next to him. That's a cutup. I was sitting in a lunchroom in New York having my doughnuts and coffee. I was thinking that one does feel a little boxed in New York, like living in a series of boxes. I looked out the window and there was a great big Yale truck. That's cutup—a juxtaposition of what's happening outside and what you're thinking of.

So that influence, the influence of your media cave with its neglected little boxes—it really couldn’t be helped. Did you also find explicit use for the Burroughs/Gysin cutup method? Or was there perhaps something of your own invention at work?

Oh yes, I explicitly used cutups for this novel. Lots and lots, especially during the big push, the heavy lifting that took place in ’06. And I’m talking cutups in the classic Burroughs/Gysin sense, two texts sliced down lengthwise and reattached with their opposites: AA and BB become AB and BA. Then you strike out the word fragments caught in between so it looks like a crooked seam. They’re great aesthetic objects, just on their own. You may notice a few words and scenarios in the OEC crop up again and again—I think some of the sections involving day laborers—and that’s the residue of the cutups. Eventually I rewrote things so much that the effect was mostly obliterated, but it did help generate content, which was my reason for doing them. I wanted to come up with ideas that I couldn’t simply conjure up through ordinary means—out of thin air, the old fashioned way.

This is in addition to a number of other techniques I used to write the book—crazy voodoo séances, assisted meditation practices, panic naps, Oulipo games, and outright divination. But never again! Now I know better and I hope I never have to use this stuff. The thing is, back then I didn’t know what I was doing, and the novel was taking so long to write, each page took an inordinate amount of effort. So cutups, substitutions, MadLib-type exercises were a way of generating stuff. The “assisted meditation practices” I mention is something my friend Sam turned me on to called Holosync. It’s a subliminal aural effects soundtrack you listen to through headphones that’s supposed to break your mind open to hitherto unknown possibilities. Outwardly, it’s just the sound of rain, but underneath, these tones are working their magic on your skull. About 30 minutes of that puts you in the zone. I would say that Holosync allowed me access to the characters in a very deep way, and even helped me solve a problem or two with the story. I wouldn’t not recommend it.

The most stunning transitions in The Orange Eats Creeps do seem conjured, perhaps supernatural. You published a fairly lengthy excerpt of The Orange Eats Creeps in Black Clock 3 in 2005, and between that excerpt and this book, it looks like a great deal of your heavy-lifting was not so much putting things in place as it was tearing things out of place. The narration of the excerpt is disjunctive, but the reader can pretty easily track the narrator’s logic; whereas, in the book, where the reader ends up by the end of any given paragraph is mostly beyond conjecture when s/he starts it. Is there any stuff that you wish the book hadn’t churned up and spit out? Things you wish had just been cut up rather than cut out? Perhaps this is the time to ask about the vampire business—a popular question I would guess, maybe just an annoying one—why and how this word, this construct seems to vanish halfway through the book, as though we had gone through a mirror and it was no longer visible to us?

I knew that it would be way less interesting if they turned out to be merely vampires. Sure I started with that construct because, in 2004, before Twilight mania, vamps seemed to still have an element of cultishness. I was aiming for Lost Boys vampires, by the way: emo, to be sure, but with a scummy, Jim Morrison-with-V.D. kind of thing going. I hadn’t seen Near Dark yet, but that’s pretty close to what I was going for too. Dangerous dirty people.

Quite a lot of stuff was cut from the novel over the years. Maybe 75-80 pages all told. It’s such a delicate balance between—not too much vs. not enough—but one kind of too much vs. another kind of too much. It’s supposed to be swampy and overwhelming, but I didn’t want it to be such in a way that took you out of the story. I hope I have succeeded. Everything that was ever deleted is in a Word document crypt somewhere on my computer.

I think that you have succeeded: reading, I was constantly astonished to find that, even though I couldn’t really track how I got where I was, I never felt I ought to go back and scan for sense; it was utterly unnecessary—the sense had carried through, sans the more maudlin or mundane causality of most fiction. All of the rereading I’ve done has been for the sheer pleasure of savoring your book.

“Lost Boys” is very much Santa Cruz/Northern California coast, just as “Near Dark” is very much Oklahoma/Old West. Living in Portland, I can attest that The Orange Eats Creeps is very much Oregon west of the Cascades. Why the Pacific Northwest? Why, specifically, Eugene-to-Portland, do you think? Is it the people or the place?

The story needed a moist foresty landscape to take root, someplace potentially creepy. It’s no accident that “Twin Peaks” is set in the Pacific Northwest, as Orange is for a lot of the same reasons. The idea that hidden unnamable things can lurk in the dense crush of wet foliage. Of course, to a large extent, I’m displacing Santa Cruz lore up north. See, I’m not ready or willing to write about my hometown directly, so calling it somewhere else allowed me just enough distance. Maybe a Santa Cruzan would find it obvious that it’s as much about that town as it is about Eugene or Salem. That said, I’m glad it holds up for a Portlander (Portlandian?). That’s really great to hear. I’ve long been captivated by the whole region. It’s so beautiful, wild, mysterious and dramatic. A lot of great bands come from there. It was a place that many Santa Cruz friends fled to when our town got too expensive, so it always held promise for a better kind of life, even as it dashed those hopes for many. I would have to add that I’m also writing about an “Oregon of the Mind.” A fairy tale landscape sown by the subconscious. Other places, like Detroit or Marfa, however rich with meaning, don’t give me as many ideas along those lines as Portland, Salem, Eugene do.

Santa Cruz definitely has its own mysteries—every time I drive south through those hills along the Santa Cruz Highway, I’m definitely thinking hidden, unnamable. Maybe that’s just me.

If you’re not willing or able to write about Santa Cruz yet, what are you writing? In one of your bios, it says that you wrote a collection of essays, at least one of which was also in Black Clock, a really great essay that moves from GG Allin to Grace Slick, via Wendy O. Williams and Nico. Any progress there, or are you on to other things?

Actually, I am able now! The novel I’m working on is set in the Coast Range/South Santa Cruz County area—but in the late 19th Century. Yeah, that GG/Nico/Williams/ Slick essay from Black Clock was one of a series I called the “Burnout Book.” There was also a piece about low period Lou Reed (circa “Sally Can’t Dance”) and Joe Dallesandro’s film persona, and one about Prince protégé Vanity and some other stuff I can’t recall now. It’s not something I have continued working on, but I wouldn’t eliminate it as a possibility in the future. Any suggestions for burnouts?

The Burnout Book! Really, sort of an inexhaustible topic—the 80s alone are impossibly deep. Speaking of “Lost Boys,” why not the Coreys? Is that too obvious? Kiefer Sutherland, too, though he seems to have pulled out of it somewhat. I have my doubts. Dee Dee? Axl?

Coreys and Kiefer no, Axl maybe. One basic criterion is that they have to rock or have mystique to burn. Elvis Presley would qualify on both counts. Elvis and Priscilla together, an irresistible mix with lots of gaps that invite wild speculation—like, how exactly did they come to meet? This is in keeping with my enduring fascination with some of the classic groupie types, Pamela des Barres and Cyrinda Foxe, obviously, but I would include Priscilla in that category too. You want to read a bummer of a book? Check out Rock Wives by Victoria Balfour. Outwardly, it’s a somewhat fluffy in-their-own-words how-I-met-Brian Jones kind of romp, sweet stories with a twinge of heartbreak. Wistful, nostalgic. Upon closer inspection, though, it’s a dazzlingly shitty compendium of bad behavior and exploitation, soul decay in slow motion. Only Smokey Robinson’s wife comes out not totally screwed—although the book was written in the late ‘80s, who knows what happened to her.

Well Grace, we’ve managed to go from Los Angeles to Portland and back down to Los Angeles. Sort of fitting for a book that is, at its core, peripatetic, a kind of quest-narrative. Anything you’d like to add?

I would just like to say thank you, Gabe, for your great questions. And who knew that this interview would end with a mention of Smokey Robinson’s wife? I just looked her up; her name is Claudette Robinson.

Thank you, Grace.