|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

Movie |

|||

|

I Bet I Can Find a Million People Who Hate Slab Cakes |

|||

|

Blue Fish Apocalypse #12 & #35 |

|||

|

Suffolk Downs |

|||

|

Kate Petersen’s work has appeared in The Iowa Review, The Pinch, Brevity, The Collagist, Quarterly West, Phoebe, and Best of the Web 2009 (Dzanc), among others. She writes for PostScript, and lives in Minneapolis, where she waits for winter. |

|||

|

|

|

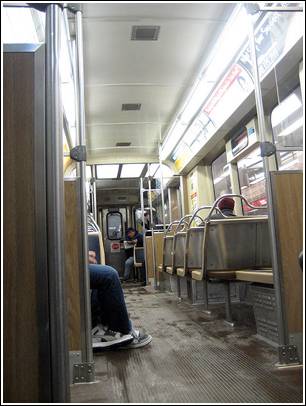

Photo by Ryan Molloy |

A man on the blue line inbound from Wonderland scratches a lottery ticket. He stands, holding it cupped in his palm like a compass, uses a nickel from wherever. Here is my life, he thinks, flicks the waxy leavings to the floor with his finger. He’s forty maybe, gray only in the beard yet. The circles are arranged like balls in a billiards rack, except they are all one color, same as the coin. The man does not know the difference between telling himself something and thinking it, but there must be one, he knows that. Here is my life. He does not know where the words came from. The numbers don’t add yet, three circles left.

The woman sitting across from him is going somewhere. There’s a suitcase, books and shoes, maybe a car for her to drive when she gets there. In speech, her parents’ house is still Home, though she has been on this coast four years now, like a woman who says husband out of habit and must be reminded of the prefix by friends, years after the divorce. She watches the man with the scratch ticket, the shameless voyeurism that comes from traveling alone. A magazine lies open in her lap, unread, a prop. Speak when spoken to, that is what she believes about herself. It is thin, but it has served. She is young enough yet—thirty or less—to pity the world its infirmities.

She sees Suffolk Downs on the train-map above him, can smell the beer and manure and cigarettes. She sees the man standing in line on even the worst days, pulling the money clip from that blue vest, taking a seat halfway up. The silver clatter of hooves he must dream of. Stays for the last race, she’s sure, misses work some days, if there is work. It goes Orient Heights, Wood Island, then hers, Airport. She looks at his shoes and hears the starting gun.

Nothing. The man creases that one, takes another from his pocket, wipes the edge of the nickel on his jeans. He looks up when the doors open, Suffolk Downs. He’s never been to the track. The only horses he’s been around were the paints his aunt raised in Washington, trail rides they took summers he was a kid. He feels the nickel between his fingers like a rein, does not know why the voice goes on—Here is my whole life—but he lets it, the way he let it that night, walking home through snow the first time.

It had been coming down for hours, hard, the plows weren’t out yet. His first winter in Boston, the flight to Tampa and everywhere else cancelled. She might have through Sunday, the doctor told his father, but the airlines won’t do anything until there’s a wake. All the flights had been cancelled the next day, anyway, the snow wasn’t supposed to let till sometime after dark. I’ll call you, his father said, which was like stop trying, so he’d taken the train back to Davis, where he kept an apartment near Tufts. The stairwell smelled chemical, like the salon he’d gone to with his mother as a kid, a mix of permanent and cream rinse and stale coffee. He pushed the clothes onto the floor and lay back on his bed, leaving the door to the hall open. He would kneel on the plastic chairs while she was getting her hair set, pull the dryer helmet over his head and press on his eyes until the back of his lids sizzled white and gray. He was trapped in the lunar lander, the moon so big in the window that space was gone, and earth, and it was just him and his mask with the pinhole vents and the moon so close he would either crash or never reach it.

The train chimes and brakes, people take their bags. He undoes each circle now remembering how it was to walk back that night, small numbing strides down the middle of streets, Irving to Mason then Whitman. Couldn’t hear his own footsteps even, in the deepening snow, but he’d felt them through his boots like a pulse, nowhere until the finger touches its own wrist. Here is my life. The sentence calmed him. Buildings and trees threw their shadows out before him like blue condolences, and in the middle of Broadway he’d stopped to listen to the white absence of cars and wheels, to a single shovel against a walk somewhere, each scrape a wager on the snow’s final hour.