|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

A Letter to Amandas |

|||

|

Interview with a Union Soldier, Newly Dead |

|||

|

Slut Whore |

|||

|

The Zoo: Two Stories |

|||

|

J. Robert Lennon |

|||

|

Kyle Beachy |

|||

|

Andrew Ervin's first book, Extraordinary Renditions: 3 Novellas, will be published next year by Coffee House Press. He has fiction forthcoming in Monkeybicycle and Conjuctions. |

|||

|

|

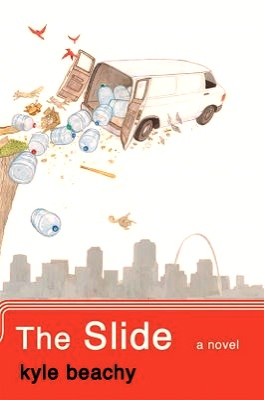

Kyle Beachy's debut novel The Slide is the kind of first novel that makes you happy for the presence of books in the world. It's weird and wild and hilarious and touching all at once. This book moves. After his graduation from college, Potter Mays comes home to St. Louis to live with his parents, whose marriage is nearing collapse. Potter's girlfriend Audrey is off in Europe with the beautiful and bisexual Carmel. His best friend Stuart has invented a new and mostly useless career path for himself (Independent Thought Contractor), which seems to involve nothing much but sitting around his parents' pool. He takes a job driving a bottled water delivery van. The people he meets, the things he sees and the city itself come together in unexpected and wonderful ways to push Potter down the long slide into adulthood.

You can read the first chapter here.

Kyle teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has published fiction in The 2nd Hand, decomP, Otium, as a Featherproof Mini Book and right here in Hobart.

We spoke recently over email.

It's a thing, topography, but not as much of one as people might think. San Francisco might be the most famous skateboarding city in the world. Guys will stand at the top of hills and time the stoplights below so they can bomb down uninterrupted. This scares the piss out of me. But the SF legend really grew from a flat, expansive brick plaza with a few big concrete steps in the middle. Some of the most fun I've had on a skateboard took place in an empty church parking lot. The real challenge of Denmark was finding pavement. We had trees and dirt paths, gravel paths, a lake, fields with goats and sheep. That part of Jutland had some glacier activity in the past, so there are actually these rolling hills around the lake, even a ravine, which provided the perfect excuse to politely ask one of the Danes to please pronounce the word "ravine." Almost always funny.

The Slide is a remarkable novel. One of the things I loved about it was the way the very real aspects of the novel had a way of sort of opening up into the unreal. I'm thinking in particular of Freddy, of course, but also a character like Edsel, who is really almost mythical in his size, with his beard and prowess. I know you recently taught a course at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival on what you've called"a-realism" or anti-realism. Can you discuss this in terms of The Slide?

Thank you, Jensen. I like the idea of opening up, or allowing the unreal to grow from within the real. If the point of story is to provide some kind of order to the world, it seems to me irresponsible and negligent if the story refuses to at least negotiate with fantasy. These are the mysteries we cannot simply name. I like to lean all of a story's weight on reality, and then look to see where stress factures emerge — the interstices Melville wrote about. In these you catch glimpse of a secondary order, something hidden and mythical. In The Slide, reality and fantasy are indexed, or failed to be indexed, by one character in particular, who shows signs of possible unreliability. And given the nature of Potter's questions about love and adulthood and communication in general, this issue of reliability is crucial.

I like the way you approach these ideas in the novel. There is a lot focus on the growing distances between characters. Potter and Audrey, of course, but also Stuart and Potter, and Richard and Carla. To me this allowed two things to happen. The hidden and mythical that you talk about seeped through in great ways; and also it charged Potter's newer relationships (like with Ian, for instance) with a strange kind of energy to interesting, and catastrophic, results. What were the challenges (or benefits) of balancing Potter's unreliability with the exploration of these rifts, these distances?

I think you have to approach distance as a subjective concept, something relative. The space between you and I depends on who you ask, when. And whether I've had coffee. Or if I'm sad and I feel lonely or I'm happy because I feel loved. Which means that unless we're dealing with an all-seeing, objective narrator who clarifies exactly how each party views closeness or distance, it's always unreliable. And flexible. So, to firmly plant a narrator within one character is a restriction, but it also obliterates any pretense of fairness. It allows for the gradients of madness that define a life.

I love this: "the gradients of madness that define a life." You really get a sense of this being exposed in Potter as the novel progresses. Which I guess is kind of the crux of things here, right? It's the summer after college graduation and he's faced with all these events and relationships that are threatening to strong-arm him into adulthood. Let's talk about terms like "coming of age" and "traditional narrative" and the ways you work within and also against them.

I think one big lie of modernity is that adulthood is permanent — like a too-small turtleneck you squeeze into and then never take off. We age and accumulate responsibilities, yes, we mature and grow wiser. But we're not fish that can't swim backward. We regress. And the model in which one experience changes a person and gives her a new perspective, he steps out of a cave into the light, she's ready to productively contribute to society... this seems crude.

Nor do I really adore the way people are so quick to label something as traditional versus experimental. The terms are loaded and often self-serving, like Drew-Lynn Eberhardt in DFW's "Westward..." insisting that she's a post-modernist. My goal was to write a narrative that moved quickly and linearly and fluidly while pushing against some of the coming of age tropes listed above. Whether the result is traditional or experimental is something I'll leave up to people who speak in those terms.

The Slide is also a very funny book. What about humor makes it such a vital tool in fiction? That's a stupid question. What I mean to get at is this: you manage to be funny both in situation and in language here. A lot of the narrative itself is pretty hilarious (when Potter returns to the winery was a high point for me), and all of the relationships Potter navigates here are funny in some way. Just to pick out a few more examples: Stuart's "career" as an Independent Thought Contractor, the Ad. What were your goals with humor in the book? Was it the natural result of exploring the textures of these relationships?

That's a really good way to put it. I know whatever humor there is was born, definitely, of the sadness. But it wasn't some kind of attempt to counteract or balance sadness. It's humor that carries sadness's long maudlin train. It's the goiter on sadness's neck. I suppose it's partially satirical — another example of pushing against certain realities. Hyper-advanced capitalism and what that meant to our country's emergent labor force eight years ago. But satire is a drunk who requires something sturdy nearby, or else he can fall into a puddle of his own sick.

There are a lot of characters in the novel. Some of them are in it for the long haul and some appear and then disappear. And some of them we only hear about and never meet. What are your thoughts about the expectations readers have about a character's entry and exit from a novel?

Individual lives are tiny little things. Define a given period — here it's three months — and there's no end to the contact points them. This is simplified, but the basic point is this is our social world today. We're clouds. We brush up against one another in all of these different ways, sometime we combine, and we keep moving. I also admire the old adventure motifs structured into episodes and encounters as the hero moves from challenge to challenge. The Zelda model. I'm not sure how either of these ideas align with readers' expectations. I suppose if a character's departure is disappointing, it at least means that some kind of connection has been formed. That's what you'd hope for.

In his blurb of the novel, Ron Currie says The Slide is about "[t]he decay of both the American city and the American family." I like this take. Talk a little about the ways The Slide deals with this idea of The City, or St. Louis in particular. You're from St. Louis, right?

I am. My folks are there, my sister and her family, my dearest friends and some great asshole skateboarders. I'm back often. And it's the city's fault I began writing fiction — I always had this lingering sense that there was something interesting going on there. The legal division between city and county and how it affects crime stats and fiscal. Dual development downtown and out west. The state of baseball fanaticism. The way people drive. They felt connected. So when I began fiddling with a novel, all of these found a place in the story and they felt more central than mere texture, and it became necessary to let the urban and familial stand side by side. Because ultimately they're the same issues: selfishness, obligation, resentment, love and Love and "love."

Potter's father, Richard, is the Director of an organization called St. Louis Hooray! which is focused on urban renewal. There are some big metaphorical parallels there, of course. How important was it for you to address these ideas of urban renewal or gentrification? The changing urban landscape reflecting the emotional journey of character?

They reflect because they're the same. Or really, they're fractal. These different levels or worlds each contain and reflect the flaws and strengths that make us human. The internal personal struggle is to define and maintain a singular self among countless other selves. Sometimes this is hard. A family is a group of selves working variously with and against each other for common and discrepant goals. Some families branch for generations while others crumble under their own weight. A city is a network of families (of individuals), again with common goals and ideas, but also oppositional rifts among them. They grow and shrink. On every level there is growth and change, and also failure. And it's work, effort, in every world. So fractal because the shape of the struggle appears and reappears from every distance at any scale, from micro to macro.

You have a notable online presence at your site and in journals all over the Internet. What do you think about the online writing community?

For writing, the web provides the ultimate freedom to never justify. I don't believe anyone today can rightly complain about lack of opportunity. But is it a community? I worry this can be limiting: writing for a readership of writers, the internet as swap meet or support group. Because another beauty of publishing on the web is reaching outward to people who might not normally take the time to find and consume fiction. So I like combinations of online and print publishing, like Hobart. The innovations you see with featherproof. For me personally it's great because novels take a long time to write. The web provides a venue for everything in between, essays and short stories, blog posts and tweedles and even photo captions. Words and texture.

You teach at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where you also got your MFA in Fiction, correct? What's the experience of teaching like?

Teaching is a challenge for me. SAIC is unique because you're dealing with a certain breed of student in an environment where reading and writing don't automatically carry the same weight they do elsewhere. In my classes we look at texts as the students might look at other works of art, examining the decisions that went into each piece, asking why? and how would the effect be changed if...? and other questions that come from creative interests rather than deconstructive. Classes meet once a week for three hours, during which time I'll sweat through shirts and panic and falter and stutter and hear myself say things I can't believe I just said. It's an exercise in humility.

What's next? Are you at work on a new novel? Some blogposts and tweedles?

I come and go on the blog posts. I'm no good at forcing one out for the sake of forcing. Twaddles are more frequent because I've this secret diary slide-out keyboard on my mobile phone unit. Mainly I'm at work on a second novel. The month in Denmark was about spitting out rough work, figuring out what's going on, where the stress points are, who's important and who's secondary, and so on. The Slide is the result of much revision, and so to start something new was kind of overwhelming. The freedom of a new project is every bit as intimidating as it is liberating. Not just because the possibilities are infinite, but because early decisions dictate how everything else will follow. Now I'm getting excited as I go.

You, Bret Anthony Johnston and Kevin Moffett have a skating competition. Where would it be (home-field advantage!), what are the stakes, and who would win? Pool? Park? Bomb Lombard St.? Feel free to talk serious literary shit if you feel like it.

I will shred them in half with my aging knees and achy right heel. No, but that would be fun as hell to get a mini-ramp session somewhere. Can someone set this up? I know this ramp on the southside in a space above a car wash. Johnston is in Boston, but where's Moffett? Or we can meet in Louisville or Davenport. This is an open and respectful and official invitation to both Misters Johnston and Moffett. Let's do this. Three dudes on a ramp drinking from tall boys in coozies. Best blunt to fakie wins blurbs from the others. Oh, this is gonna be rad.