|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

haikus |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

C.J. Hribal |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

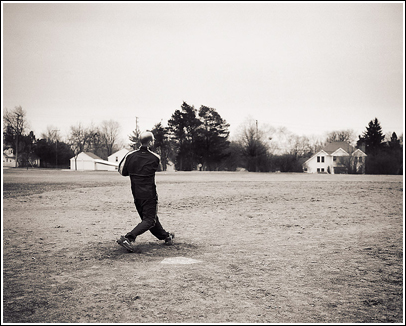

Photo by Colin Blakely |

A friend once told me a story about a kid he'd known who played right field and caught flies. Not fly balls – this kid hated Little League, hated his father for making him play, was afraid of the ball, and of the other kids on his team – but actual flies, houseflies, or whatever kind of flies were out there in right field.

It was a beautiful day, that day at the lake, and my friend laughed as he told the story – not in a mean way, just because it was funny. Standing in right field and catching flies instead of fly balls: who wouldn't laugh, remembering that kid? We were all decades past Little League at that point, and my friend had been very good at baseball. I laughed too. My friend flipped the burgers, headed over to the cooler for some beers, squatted down to whisper to his wife where she lay sunbathing with her friends, knelt to kiss her neck, and now I stand in the shade and squint at the sun and imagine it like this:

A fly comes buzzing along, and the kid checks to make sure that no one is looking his way – the coaches yelling about something that happened at second base, or else a dog wandering out into shallow left and play suspended, or else everyone (the umpire, the players, the coaches, all the parents in the bleachers) held blind in the vast twitchy boredom that is a change of pitchers. The kid shucks his glove, waits motionless for the fly to come back, and of course it does, they always do, it nears and nears, perhaps attracted by the smell of his nervous sweat and hatred, and as it lands on his outstretched arm he sweeps his opposite hand across the surface of his skin with impossible deadly speed and now his hand closes and the fly is trapped.

The afternoon is very hot even here in the shade, there is no reason for it to be so hot, and there are so many possibilities. Sometimes the kid cups both hands together and shakes them, the fly now drunk and baffled in the dark sweaty space between his palms; the kid listens to the sick dizzy buzzing, scoffs and shakes his cupped hands again and opens them just long enough for the fly to think it is free and then smacks his palms together and stoops to wipe the messy smear on the grass. And sometimes he pincers the fly between forefinger and thumb and tears off its wings. And sometimes he stands in that expanse of arid green, and holds the fly cupped without shaking it, and listens to the steady drone of the world, and before he has decided exactly what to do (though that moment that bright future surge of action never involves any actual decision, is instead simply whatever happens to happen through his body) there is a shout, and then more shouts, two hundred and forty voices shouting his name and the ball is coming he knows that now and his hands open and the fly escapes and he holds his hands over his head and his mind is a searing black flash of not thought exactly but a knowing of what is coming the pain as the ball strikes his face but now no, the sound, the thud as the ball strikes the grass in front of him, he sees the ball bounding up over his head and turns to follow it and the flash is now gray and searing and still not thought and still knowing what is to come his teammates and their scorn and he runs and the ball rolls and he runs and the ball slows and he runs and it stops against the fence and he arrives and gathers and bobbles it and then throws as hard as he can, looks down and knows and looks back up and yes, his throw errant of course, missed the cut-off man, had nothing to do with the cut-off man, lands now near the enemy team's dugout and they are giddy, laughing, his own team's first baseman scrambles toward the ball, bare-hands it as it rebounds and whips it to the catcher but not in time.

So. An inside-the-park homerun. And his teammates stare at him. He pulls his cap low and peers out from under it. The gurgling swell of voices from the stands and his father's voice is not clear among them but he imagines that it is. His teammates' voices are clearer but they are not talking to him and so he does not listen. His coach's voice is clearer still and the words are intended to be encouraging but everyone knows what they mean. The kid stares at the grass and thinks about the fly he caught and lost, that fly off flying somewhere now, and he smiles but there was no barbecue, no lake, no sunbathing. I'm sorry. I don't know where that came from. I haven't spoken to my friend in years.