|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | blog | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

haikus |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

C.J. Hribal |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

If the game of baseball is a narrative in numbers, try this one on for size: on Saturday March 30, 2008, 115,300 people showed up at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for an exhibition game between the Boston Red Sox and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

It's the biggest crowd to witness a baseball game anywhere in the world. It's also a freakishly large number of people to be gathered in one place for a short period of time.

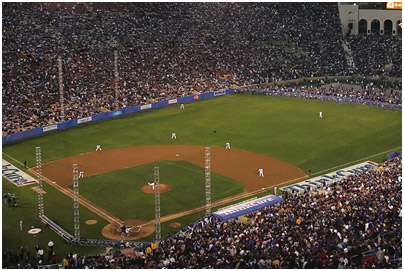

What does 115,300 people look like? It's this times six. Picture thickets of burly men queued up for everything from beer to funnel cakes. Imagine traffic jammed on multiple freeways from every possible direction. Try, if you can, to convince yourself that $60 isn't all that much to pay for premium parking. Listen to the Nuremberg-esque sound of one hundred thousand souls singing "Here we go, Dodgers, here we go!" It was enough to transform a decrepit college football stadium built in the early '20s into a true Coliseum worthy of chariots and lions.

In 1958, the Dodgers left Brooklyn. Dodger Stadium opened in 1962. During the intervening years the Dodgers played four seasons at Los Angeles Coliseum. Due to its unique dimensions, the left field fence was just 250 feet from home plate. To compensate, a 60-foot-high fence was erected from left to center field. Anything that went over the fence was considered a home run; everything that fell short was a live ball, playable off the fence.

The players adapted. Wally Moon, who proved adept at the inside-out stroke required to send balls into the bleachers, became famous for his "Moon Shots" and Duke Snider earned $200 bucks in a wager by throwing a ball clear out of the Coliseum.

In spite of its odd dimensions, the three games held at the Coliseum during the 1959 World Series hold the top three spots in the record books for attendance at World Series games. It was a good time to be a Dodgers fan and Dodger-mania swept the city.

When I first heard about the game, which would kick-off the season-long commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Dodgers arrival in Los Angeles, I knew it was something I had to see. I became a Dodger fan at the exact moment when the Clash's "London Calling" got stuck in my truck's tape player and I had to switch to radio during excruciatingly long commutes. There are fewer commercials during baseball broadcasts, I reasoned, but eventually the words that came from Vin Scully's golden throat coaxed me into caring about the story he was weaving out of numbers.

Relatively recent renovations to the Coliseum have shortened the distance from home plate to the left field fence to 201 feet. That's little league distance. As Kurt Streeter wrote in the Los Angeles Times "every Dodgers and Red Sox player on the field Saturday night could hit a ball that far while dreaming." Even USC football coach Pete Carroll found time to knock a few out of the park during batting practice last week.

I attended the game with my brother-in-law, David, and cousin by marriage, Jose, and we each brought our daughters ages 7, 4 and 11 months – the most precious statistics of all.

David grew up in the shadow of the Coliseum in a house on Broadway that was razed to make room for a factory. As we made our way to the stadium he pointed out where his abuelita used to live and the mercado where he bought chips and ice cream.

Our seats were in section 30, just beneath the arches at the peristyle end of the Coliseum where the Olympic torch sits. Numbers printed on masking tape marked our seats in the "benches" that were more like curbs.

We were so far away from the field we couldn't make out the numbers on the players' jerseys nor hear the crack of the bat when it made contact with the ball. The only scoreboard was directly behind us and we had to turn all the way around to check the count.

None of which mattered. The Dodgers rank and file was in an exceptionally festive mood and Red Sox fans were mellowed by Corona, carne asada tacos, and sunshine. There were never less than a dozen beach balls in the air. Sandy Koufax, Fernando Valenzuela, Duke Snider, Wally Moon, and Kareem Abdul Jabbar, who lobbed one of a dozen ceremonial "first" pitches with his patented skyhook, all had their moments in the sun. Future Dodgers star James Loney even hit a moon shot over the left field wall, one of the few memorable aspects of an otherwise meaningless game.

When the Dodger fans did "the wave," which usually annoys the hell out of me, I was amazed by the sight of all those tens of thousands of people moving in concert. As it swept around to engulf our section it sounded like a tornado had touched down on the stadium. My daughter loved it. "Again, again, again!" she screamed, gleefully caught up in something so much bigger than all of us.

But the moment I'll never forget is when Vin Scully stood at the lectern to address the crowd and the fans rose and gave the man who has been with the Dodgers for every day of its 50 years in Los Angeles a standing ovation. When Mr. Scully, who would eventually say he is simply "an ordinary man who was given an extraordinary opportunity" tried to quiet the crowd, the masses refused to listen and cheered all the louder with gratitude, admiration and love. The game may not have mattered, but for 115,300 souls, the gathering meant nothing less than everything.